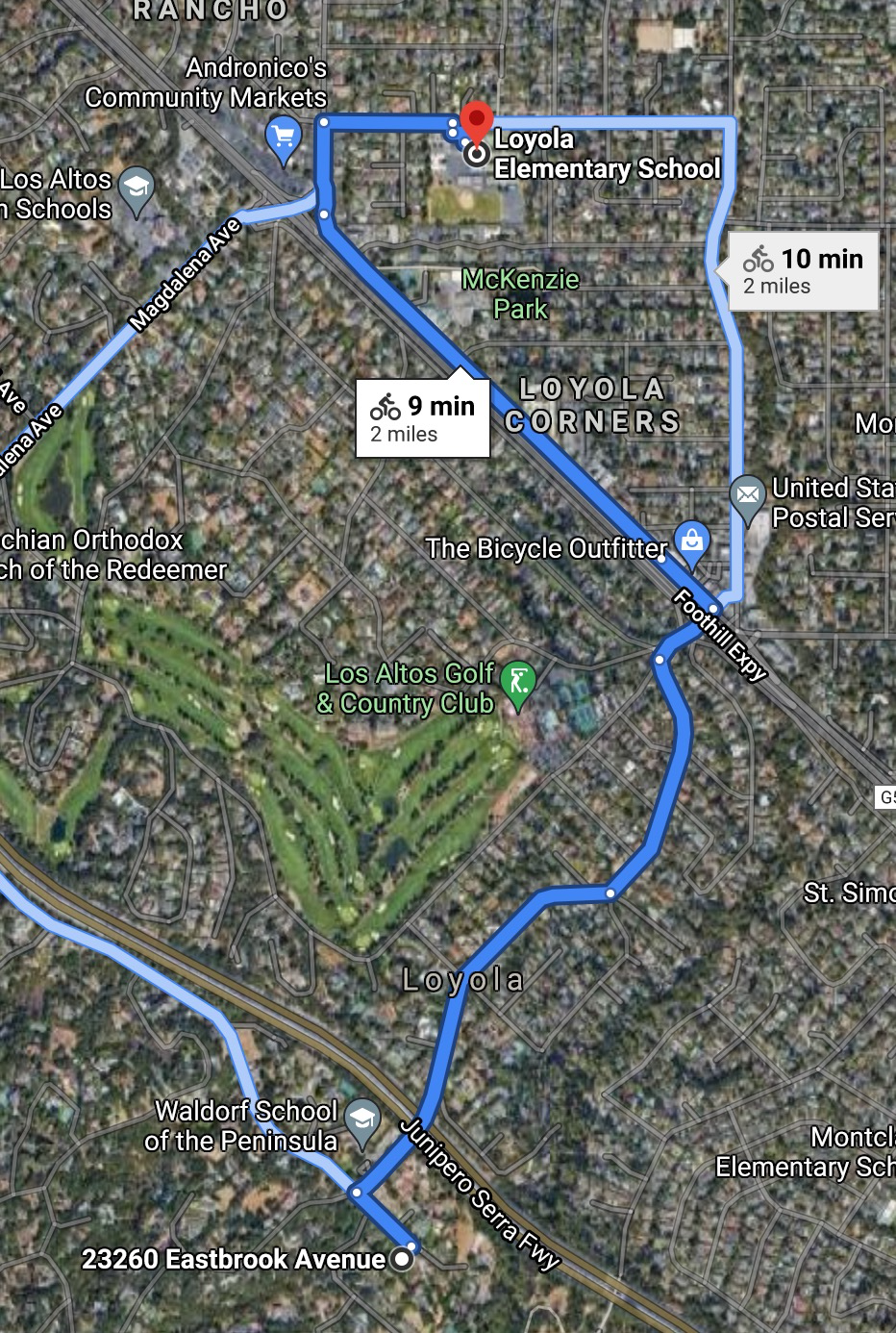

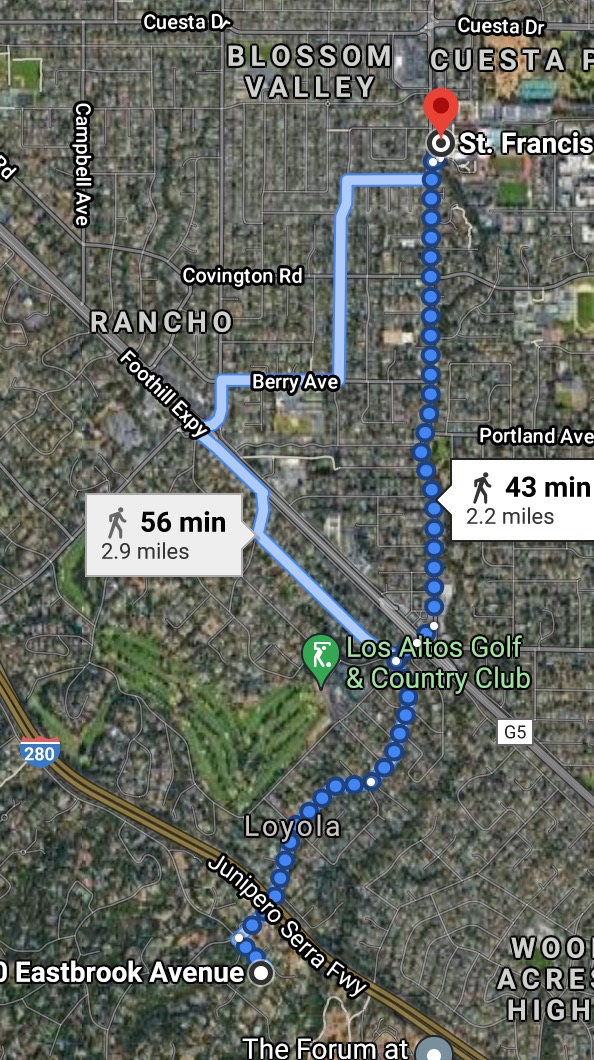

In 1956, when I was eight, we moved from the flats up into the hills. To Eastbrook Ave. We moved from classic fifties suburb to rural, although less than four miles away. Oddly rural. It was barely half a mile from the Los Altos Golf and Country Club, and a one-mile bike ride to Loyola Elementary School. Five miles to Main Street in Los Altos or to Castro Street in Mountain View. But still, rural.

Eastbrook Avenue was then a one-lane, poorly paved private road that ran a few hundred yards from Mora Drive south southeast to Permanente Creek. It started in a small flat valley just about where the landscape started to rise to the west up to the crest of the coast range at Black Mountain. To the east was an open field of tall weeds, waist high to a kid, for maybe three hundred yards before it rose slightly to an orchard on a hill across the way. To the west, chaparral covered hills rose steeply from our back yard, to coast range tree-covered mountains topped beyond the horizon at Black Mountain, which we heard about, but couldn’t actually see. To our right, if we looked out on the field from our house, the road dropped sharply down a hill to an even smaller valley fed by Permanente Creek, a year-round creek that was never wider than five or ten feet, never deeper than a foot or so in its deepest pools, full of water spiders, frogs, in inch-long fish. There was a house on the other side of the street and down from us, riding the hill. And there were two houses at the bottom of the hill, near the creek. The hill that started in our back yard and dropped down to the creek 200 yards below was a small part of the famous San Andreas fault.

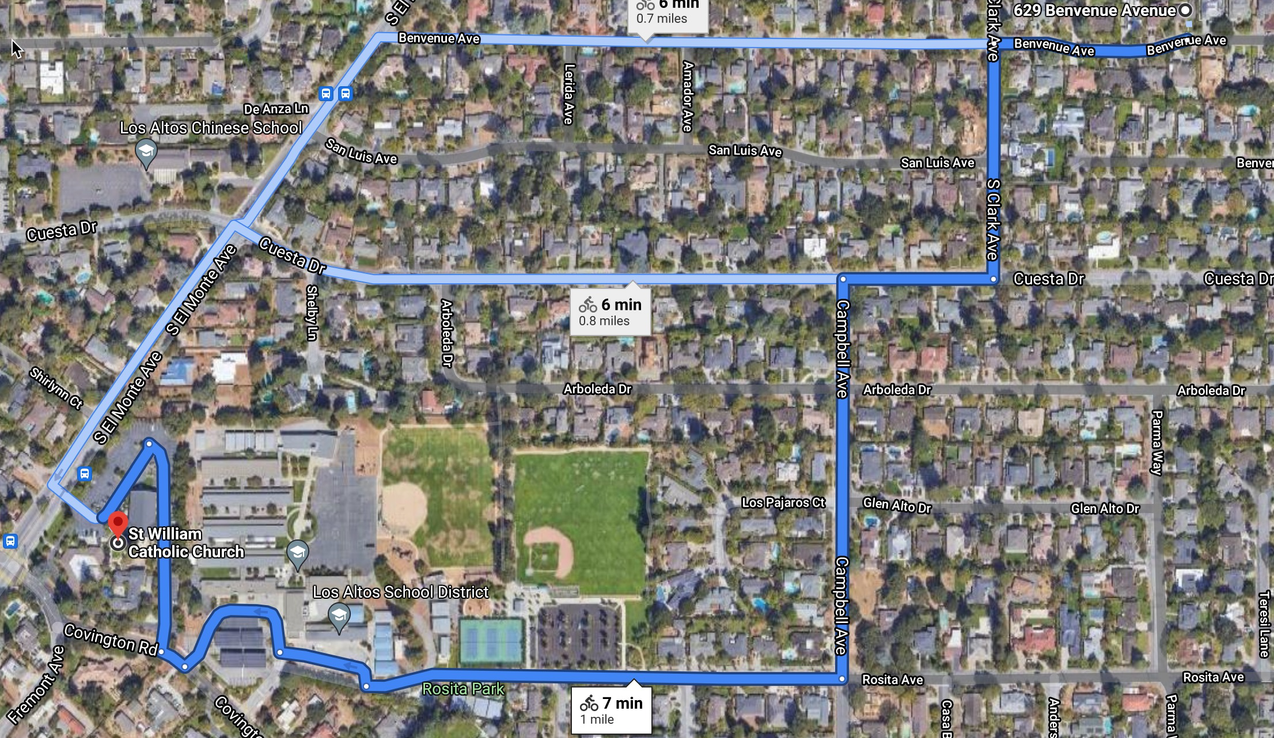

I most often rode my bicycle from there to Loyola School, about a mile. Sometimes I took the long bus ride that wound its way around the hills above and then dropped down Mora Drive to leave me off at the corner. Then I had a short walk down the street with the open green fields to my left and the one other house, before ours, to my right. I remember it with the sky bright blue, the evergreens around the neighbor’s house dark green, the open field a mixture of grass and grain colors, plus highlights of bright yellow when the mustard weeds were open. And when I say skies were bright blue, the field green, I mean real colors, as if you wouldn’t believe them on a postcard picture. We knew about smog, back then, in Los Altos and thereabouts, only because we’d seen it in Los Angeles. We’d driven through Los Angeles in the summer, on the way to Newport Beach, squinting, shocked by the strange haze that blanketed the whole area on summer days, smelling like exhaust and making eyes water. Smog was a local geographic phenomenon limited to Los Angeles. Or so we thought in the Bay Area, 400 miles north of that, blessed by crystal clear blue skies.

When we moved there, I had a sandbox, a yard to play in, a two-year-old brother who often followed me around, and a 10-year-old brother who liked chess and opera. No other kids lived nearby. I chased frogs by the creek, and snakes in the chaparral above us. I kept lizards when I could catch them. I rode my bike to the pet store at Blossom Valley Shopping Center (halfway to Mountain View) and bought white mice and turtles. My best friend from Benvenue would come up for sleepovers occasionally, but I was mostly alone. I liked the sandbox, the back yard, and small cars and trucks. And the creek, and the hills behind the house.

In a year or two, I connected with a couple of other kids near enough to play with in the summer, one of them a first cousin. We explored more of the hills and we practically owned the creek. We built forts, dams, villages with tiny cars, and throwing rocks at water striders.

It is now far from rural, by the way. The unincorporated area we lived in became Los Altos Hills. The hills behind us came to be called Pill Hill because a dozen or so doctors and families built large houses in the new streets where we used to wander through the chaparral. The field gave way to Interstate 280 first, on the far side – billed as a beautiful freeway when it was built, because of the way it wound through the hills above the San Francisco Peninsula – and then to densely packed and sadly pompous big houses that could have been the definition of what they later called Mac Mansions, big fancy houses squeezed uncomfortably into lots that left little room left over for yards proportional to the houses.

As I write this, Dad, now 100, still lives in that same house we moved into in 1956, on Eastbrook Ave. It has a small winery on the lot now. It’s been remodeled twice, and it’s on its third lady of the house. And it’s now surrounded by Silicon Valley glitz and glamor.