Category: 3. Sixties

1960: Kennedy-Nixon

Sept. 26, 1960. We watched the first televised presidential debate, Kennedy vs. Nixon, together. Mom and Dad and Chip and me. We wanted Kennedy badly. In our house it was about the first Catholic president. And Dad’s roots in Massachusetts. And his story of how Kennedy had asked to meet Mom, in Washington, when Dad testified in congress about the Korean war. I was 12. My friends and I all cared about Kennedy vs. Nixon.

If you saw those debates today, you’d be amazed. Both candidates were so polite. The complemented each other on several occasions. It was all about the space race and the Russians. Both of them stood on solid party platforms, Democrats vs. Republicans; but they had to point out the differences.

From summer through fall, there were TV commercials about it. If you get a chance, do a web search and try some of them. They seem so silly today, but they were serious to us at the time. Singing commercials with ad-like musical jingles. Kennedy commercials touted his pregnant beautiful wife Jacqueline (Jackie)and his three-year-old daughter. He was “old enough to know and young enough to do.” Nixon commercials touted his experience against the Russians. He promised to keep the peace by opposing the Russians. Peace enforced by strength.

All of it, of course, played out on black and white television. There was no color TV. We say the commercials on our shows because we saw all the commercials on our shows, with no time shifting. And occasionally we saw the network news.

The issues were clear, even to 12-year-old me. The space race, communism, Russians, and maybe, in the background, racial inequality. I couldn’t have quoted you Brown vs. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision that said no, separate was not equal. And white suburban Los Altos had no integration issues. But still, we were aware. It came up in Mom’s kitchen often.

Kennedy had a huge likeability factor. The young senator with his gorgeous wife and young daughter. His Massachusetts accent matched Dad’s accent.

As kids we were Kennedy or Nixon on the playground, on the bus, and in the classroom. The teachers encouraged it. Our opinions were almost always those of our parents.

That Kennedy was Catholic was a big deal in our house; but I didn’t hear that as an issue on television, the debates, the commercials, or with adults or even kids on the playground.

Years later I read that the election was so close that the decider might have been Kennedy shaving before the televised debates while Nixon didn’t. His five o’clock shadow made his seem somehow untrustworthy. Kennedy was also hard on the fight against communism and blamed Nixon for the communist takeover of Cuba.

For us, my friends and I, it was the first election we were aware of. Like a huge popularity contest and choosing sides.

60s: Peace and Freedom. Rebellion

What seems so important, and so different, about the sixties was the overwhelming sense that we were part of an unprecedented worldwide movement that would actually change the world. We believed it was some kind of a global springtime and rebirth, a new age of peace and love, as firmly as we believed the day would follow the night.

Or so it seemed to me. But then I have to wonder how much of my sense of the 1960s is rooted in the coincidence of my own coming of age at the same time. Do historians give it the same kind of weight? How about people who were already 30 or older in 1960? I’m not sure.

But this was my case: I turned 12 in 1960 just a few days after John F. Kennedy announced he was running for president. I turned 13 three days before John F. Kennedy’s famous ask not what your country can do for you inauguration speech. I turned 16 in 1964, just 57 days after JFK was killed; just 24 days before the Beatles’ first US appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. I was 18 in 1966 when I left home to live for a few weeks in the Haight Ashbury, the world capital of hippies, during the “Summer of Love” in San Francisco. I turned 20 in 1968, just months before the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy. I was in Paris in June of 1968 during the student riots there. I fell madly in love in 1969, was working double shifts to make enough money to get married when Armstrong walked on the moon, and Woodstock happened on the other side of the country. I fell in love, for good, in 1969. I was engaged in November of 1969 when I watched the first draft lottery — which saved me from the Vietnam war. And married, for good, just a few weeks later.

Joni Mitchell wrote this about Woodstock:

And maybe it’s the time of year

Yes and maybe it’s the time of man

And I don’t know who I am

But life is for learningWe are stardust, we are golden

Joni Mitchell, Woodstock

We are billion year old carbon

And we got to get ourselves back to the garden

But Woodstock was the harvest, not the seeds. That “time of man” feeling, the “we are golden” and “back to the garden” feeling started half a decade earlier. For me and the world.

Bob Dylan released ‘The Times They Are a Changin’ in 1964.

Come Senators, congressmen, please head the call

Don’t stand in the doorway, don’t block up the hall

For he that gets hurt will be he who has stalled

The battle outside ragin‘

Will soon shake your windows and rattle your walls

For the times they are a changin’Come mothers and fathers throughout the land

Bob Dylan, the Times They are a Changin’

And don’t criticize what you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command

And your old world is rapidly aging

Please get outta the new one if you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a changin’

We were all so gloriously young.

1961: JFK Inauguration

January 20, 1961. Three days after I’d turned 13. We watched JFK’s inauguration speech on a black and white television that Miss Alexander brought into her middle school literature classroom for the special occasion. You’ve probably seen pictures of that speech. Kennedy’s dark hair, Chief Justice Earl Warren’s white hair, both blowing unruly on a cold windy day.

The short speech gave me chills.

To those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction.

We all lived with the specter of those “dark powers of destruction unleashed by science. Cue the mushroom clouds again. That kind of talk reached the middle schoolers loud and clear.

So let us begin anew–remembering on both sides that civility is not a sign of weakness, and sincerity is always subject to proof. Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.

We knew what he meant. Listen, Russians. We all wanted peace with the Russians, but we, 12- and 13-year-old kids, didn’t trust them.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you–ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Kennedy’s words resonated. In that classroom we all believed in him. The Kennedy-Nixon debates, and the campaign, were forgotten. Kennedy was president and we — middle schoolers — believed in him. Maybe the adults were still playing out the Kennedy vs. Nixon election; but for us, this was the president. The first president we were really aware of, as we crossed over from kids to teenagers. We didn’t realize it yet, but this laid foundations for the changes to come.

1962: Bay of Pigs et al

Just a few months later, April of 1961, a US-sponsored invasion of Cuba failed. A force of Cuban exiles landed in Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. Television news knew within days that the force was sponsored and supported by the CIA and the US government. The Eisenhower administration cooked up the plan and Kennedy approved of it. Fidel Castro had evolved. We first saw him as an interesting clown who took his chickens with him when he visited New York in 1959. The TV news made him a character, with his straggly beard. He gradually settled into a folklore-laden role as a hero to a good segment of youth and politics, but a goat to the mainstream.

Kennedy believed the domino theory that ruled US foreign policy of the decade. His cabinet of “the best and the brightest” saw nations falling like dominoes to the influence and pressure of Communist Russia and China.

Cold war positioning was clear. The world divided into communist vs. Western. Russia controlled the Eastern Bloc, a collection of satellite states including East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Rumania, Bulgaria, and Albania. China was closed up to all, a lock-up communist mystery. Russia and China both influenced Mongolia, North Korea, and North Vietnam.

Historians still argue about how much US policy pushed Cuba to Russia. The official view was simple: Castro was a communist, period. He was always going to be a Russian puppet. The alternate view, which I bought into quickly, even as a high schooler in the early 1960s, was that Castro could have been much closer to neutral if the US hadn’t pushed him away so aggressively. He was marooned as a leader of a poor developing country who needed support from one of the big powers. The US turned its back on him, so he turned to Russia.

I had the opportunity later, in the 70s, to refine that view with more information. I worked with a man who had been Assistant Director (subdirector) of Economic Studies under Castro, but then fled to the US. And in 1977 I spent six weeks in Cuba doing a book. But this is about the sixties. More about Castro in the seventies.

The day after the Bay of Pigs failure, Kennedy turned his attention to Vietnam. He wanted to fight those dominoes wherever he could. That wasn’t reported at the time, but for sure, Vietnam got steadily more important, in our TV news and print coverage, from then on.

In February of 1962, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the earth in a space capsule. We all watched the mission on television, in a classroom. It was dramatic live TV as he the capsule splashed down into the ocean, and the boats from one of the big ships collected him.

October 1962. The Cuban Missile Crisis. You may have read Robert Kennedy’s journal about it, published as 13 Days; And there was a movie made too, with the same title. I read the RFK book as required reading for a business school course in leadership.

For us, at the time, it was a day to day nightmare. The news stayed on all day and in our house too. I remember the images of ships in formation at sea, and the maps and diagrams on TV, drawings of missiles and arrows pointing from Cuba to the US, arrows showing the locations of ships heading towards Cuba with missiles on board.

Every day we saw Kennedy again, staring down Khrushchev. We saw diagrams of Russian missiles headed toward Cuba and American ships blockading them. We saw mushroom clouds our heads again, more than ever. The fallout shelters and the fear we all lived with. It was on the tip of every eighth grader’s tongue. Every day we’d compare notes about what we saw on TV and what our parents said. Eventually, it ended. The Russians backed down, or so we were told. But it was a big deal to all of us, and the fear lingered on.

Throughout the fifties and sixties, nuclear testing continued in Nevada. We never heard much about it, but it was there, for years, just 300 miles or so from where we were growing up. In 1962 the US Navy dumped tons of nuclear waste into the ocean about 50 miles from San Francisco. It was stored in steel drums.

60s: Cars and cool

Mom cried the day dad brought home a used 1960 dark red Oldsmobile Super 88 convertible. “Frank, you bought a red convertible,” she cried, with heavy emphasis on the word red, which shepronounced like a guilty verdict. “Burgundy,” Dad said. “Burgundy. It’s Burgundy.”

I felt like an accomplice. I was a teenage car nut. Dad took me along with him to kick tires at the seller’s house before we bought it, used, a couple years older than new.

We did the twist at middle school dances. Chubby Checker, who made the twist popular, played in a concert at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. A couple of my girl classmates were there, and they were the envy of the rest of us.

Meanwhile, also in 1962, the Beatles were getting going in England, but we didn’t know about it. And the Beach Boys started in California.

And speaking of the Beach Boys, surfing was infinite cool, especially in California. Southern California more than Northern, where we were. But it spread to national cool and affected what we wore, what we watched, what we listened to, and what we did as well. Woodies, station wagons with wood sideboards, and especially older station wagons, were prized. Surfers had blonde hair, bleached or not, male and female.

In Los Altos, nobody I knew actually surfed. There was surfing in Santa Cruz, about ninety minutes away; but nobody had wetsuits so those were special hardy people, in the cold Northern California oceans.

What we did do was make our own skateboards and ride them down the asphalt hills. You couldn’t buy a skateboard back then. You had to buy adjustable metal roller skates, pull them apart, and nail them upside down to the bottom of actual boards. Which is what we all did.

1962: Big California Snowfall

Jan. 21, 1962. We spent two freezing hours trapped alongside an icy snow-covered highway down Merced River while Dad struggled, under the car, going numb, to free the big Oldsmobile from errant tire chains grapping the rear axle like an iron python. I sat outside with Dad, going numb, trying to help but not helping beyond just being there caring. The grinding cold was lulled somewhat by Jay’s cheery voice narrating an imaginary baseball game. “Tell that one bye, bye baby,” in an imitation of iconic Giants broadcaster Russ Hodges. Jay announced a home run. We just wanted to free the damned car from its iron ankle bracelet.

To make the whole thing worse, this was the one weekend in a lifetime that snow covered all of California, not just the Sierra. Normally the ice and snow end by Yosemite Valley, or at least in the hills above Mariposa. This time we had snow and ice all the way through Mariposa, and Merced. By Los Banos it was so bad that we had to stop for a night in a motel before we tried to get over Pacheco Pass.

We finally got back to Los Altos the next day. It had snowed about three inches on Eastbrook Ave. Martha woke Mom up saying, “the whole world is full of snow.”

This was when Chip’s reaction our neighbors’ (the Knights) building a snowman was a dismissive “typical Knight trick.”

60s: The Trees and the View

Mom also cried bitterly, off and on for days, when a new neighbor planted trees across the street. Mom knew they would eventually block that view from the kitchen window that she loved so much. We tried to convince her that it wasn’t so bad, but of course she was right, and we knew it. Dad talked to the neighbor, but to no avail. I suppose ownership had changed, or there was some other problem, because I never knew what happened beyond the fact that the trees stayed. And grew.

1962: The Last Run. Snap crackle pop.

I mentioned wooden skis and cable bindings in this story from the fifties. In 1962 those wooden skis and cable bindings failed me as I tried to play hot shot jumping moguls at Dodge Ridge. It was, of course, the last run of the day. It was also beautiful spring skiing, bright blue sky, and sticky snow. Dad was done for the day and waiting for me at the bottom with Jay. It was the Sunday of one of those ski weekends Dad used to do for me, driving up Saturday before dawn, driving back Sunday after skiing.

I was only a couple hundred yards from the top, with about a mile to go, when snap, crackle, pop, I blew a jump and found myself laying in the snow with my left foot at about a 90 degree angle from my left leg. Which hurt a lot.

Funny that it was the last run. It’s always the last run, right? But in skiing, it is often a run that was set up as the last run that ends up with the injury. You’re tired, but you want to end it well, so you push that tired. Bad idea.

This was on my brother’s eighth birthday, April 8. I had turned 14 a few months earlier.

Back then, ski patrol was a lot like it still is now, but it took longer because no cell phones. I don’t remember it taking that long, so maybe the ski patrol were up at the top because the lifts were about to close. Anyhow, I lay there contemplating pain and the weird angle of my boot to my leg for a while but then I was strapped into a sled and guided down the mountain. They took me to the first aid place at the lodge and started dealing with an obviously broken leg — both tibia and fibia, and bad — while somebody found Dad (which meant scanning the parking lot for a red 1960 Oldsmobile convertible) and he appeared.

Dad didn’t trust the bone surgeons in Sonora, the closest town to Dodge Ridge. So he had them wrap me up as best they could and drove me back to El Camino Hospital, where the docs he knew took over. He put me on a lot of drugs and I sat in the back seat only half conscious (although I still remember it) for the four-hour-plus drive. He was very angry with a local drug store that wouldn’t give him the drugs he wanted to give me, despite his medical ID; but the second one did.

The broken leg changed my trajectory in athletics. I’d been an all-star in middle school flag football and I was going to play in high school, I thought. But I was in a cast from toes to upper thigh from April to August, and was on crutches until November of my freshman year in high school. By sophomore year it was too late … I couldn’t play on the freshman team, and didn’t feel good enough to break in as a sophomore.

1963: Rainbow Lake. The High Sierras

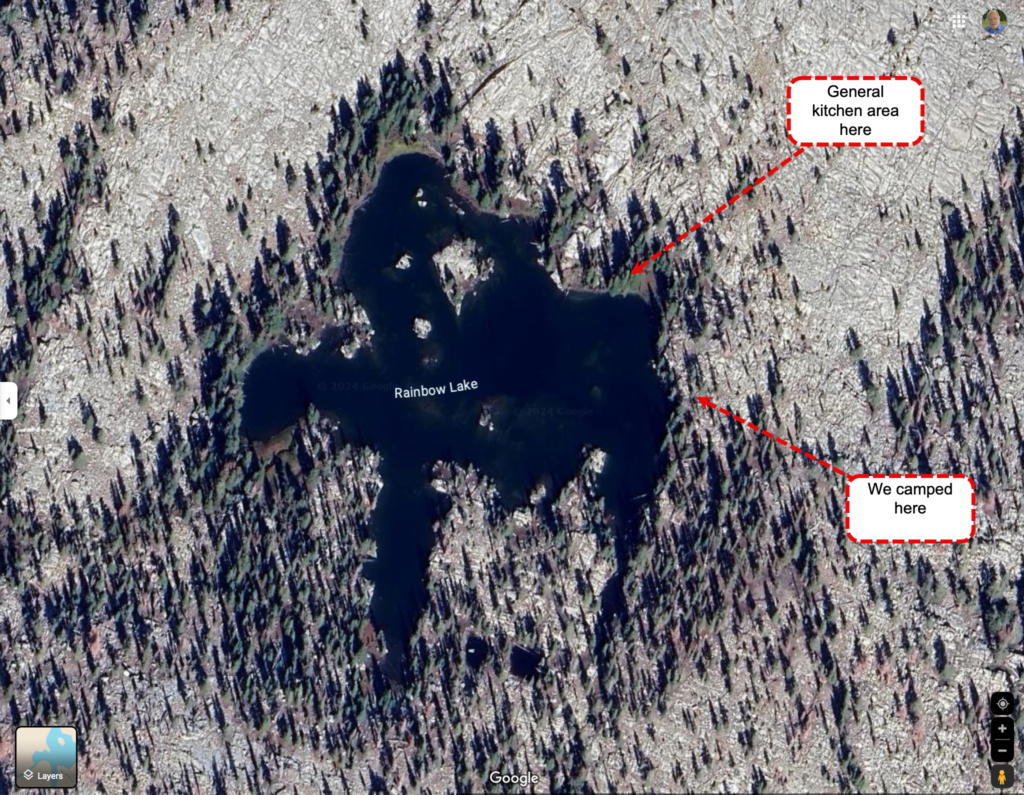

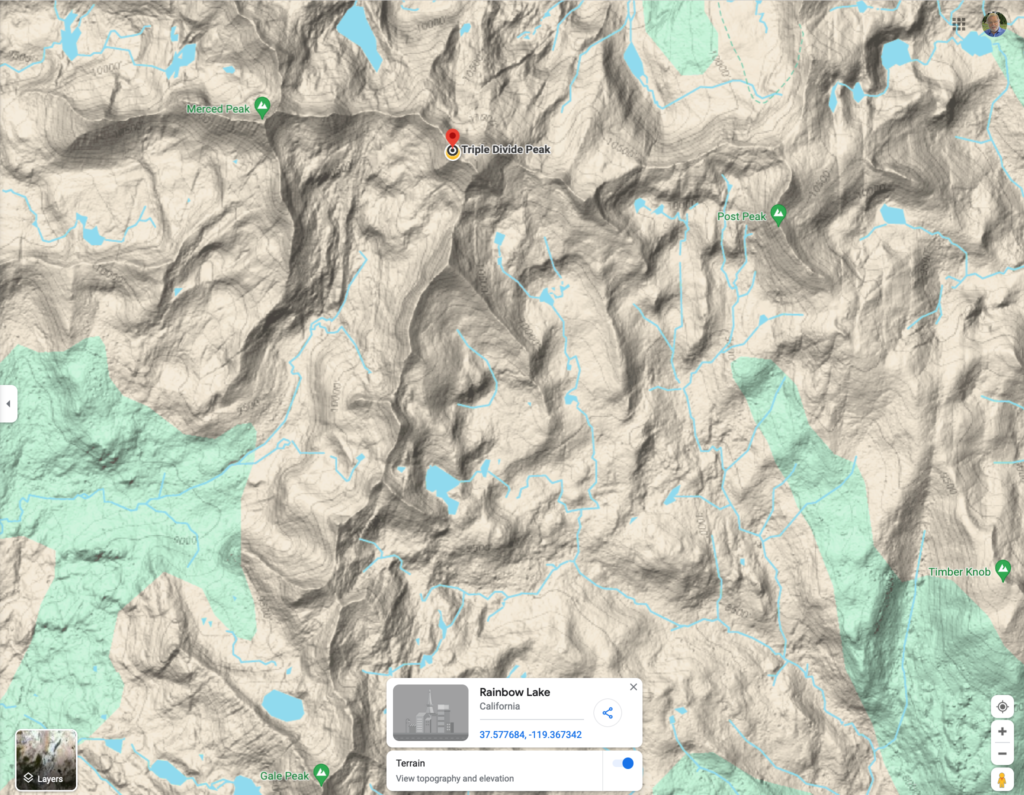

I was 15 at Rainbow Lake. Ten days in the high Sierra living in a tent by the side of an alpine lake nestled in loosely-forested granite looking up at glistening snow-patched peaks, the epitome of what John Muir called “The Range of Light.”

I think that’s Rainbow Lake. I took if off of a trail description and it’s been 60 years. It certainly looks like it.

Summer of 1963 Dad arranged a Sierra Club trip to introduce us to the High Sierra. He wanted the six of us, but Mom bowed out for arthritis and took Martha on a driving trip to visit Dorothy Gormeley instead.

We were on what the Sierra Club called a base camp trip. With mostly bad rental gear, we drove to a packing station where we slept overnight. Then the next day we hiked about seven miles, with backpacks, to the base camp at Rainbow Lake. We set up our rented tent and bulky sleeping bags.

The trip was set up for 10 families, each of which had to have teenagers. With the group of teenagers we were, even the chores were kind of fun. There was a communal kitchen and a rotation so that each of us were responsible for a few meals, divided into cooking and clean up. I was barely 15 so the tasks were simple, and — because the teenagers were spread out among the various teams — a lot of fun. We had adult supervision but we also had teenage boys and girls mixed, with chores to share; and that was a lot of fun.

At night we’d have campfire gatherings, with conversation, stories, and folk singing. It was 1963 so we had the seeds of a hippy culture, but just barely.

Most days we took hikes to nearby lakes and, on two days, surrounding peaks. Getting to the top of Triple Divide Peak was a big deal. It was a gorgeous but hard cross-country hike up through high mountain lakes and rocky slopes, with some serious football-stadium-sized snow patches. On the way down, we slid dangerously but delightfully down the snow patches on our butts. That was a long day, six miles up to the peak, and then six miles back to the camp.

We also climbed Gale Peak, which was closer, on another day trip. Both of those peaks marked the eastern border of Yosemite National Park, so we were able to look down into high mountain meadows to the west of the peaks.

This is one of my best memories, my first taste of the high sierras, which changed my life. I went with my dad and my two brothers, in 1963. I fell in love with the majesty of the high sierra, the beauty of it, the peace. I went back up on my own, backpacking with friends and on one trip Vange, for every summer until 1971, when we had moved to Mexico City. And then again, when we moved back to Stanford in 1979, we went back up into the Sierra with kids (and pack burros) every summer until we moved to Oregon in 1992. And I was back in Yosemite again in 2009, 2010, and 2011 with Megan; with Vange and Timmy in 2012; and with Laura in 2018 and 2019.