Note: this was first published in March of 2017 in Medium as US Politics: How Did we Get Here. So it was written close to the beginning of the Trump era, just a few weeks after his surprise victory in the 2016 presidential election. I didn’t know how bad things would become. This is what I saw then.

How did Donald Trump rise to the most powerful office in the world? It wasn’t just him. It was the times and the trends.

I’ve lived through 13 presidencies. Harold Truman was president when I was born. Eisenhower was president when I started middle school, Kennedy when I started high school. I went to college during Johnson and graduated under Nixon. I was married and had two kids when Nixon resigned. Our third kid was born while Gerald Ford was president. I started business school under Carter, started my own business under Reagan. Our kids grew up to the rhythm of Bush to Clinton to Bush to Obama. And now I’m trying to understand the Donald Trump presidency.

I was sure a Trump election was impossible. Bad behavior used to matter. I saw Senators Gary Hart and John Edwards disqualified as presidential candidates for marital infidelity. I saw Governor Edmund Muskie disqualified for responding too emotionally to an attack on his wife. Governor Howard Dean was disqualified for shouting too much at a campaign rally. By those standards, Donald Trump would not be president. He would not even have survived the primaries.

But, obviously, times have changed. It seems like tens of millions of bitter white people voted with their middle finger; and Donald Trump was the right celebrity at the right time. He converged with these (at least) five trends.

First: The Postwar Boom Runs Its Natural Course

Trump’s “make America great again” tapped into a deep well of discontent rooted in natural, unavoidable economics.

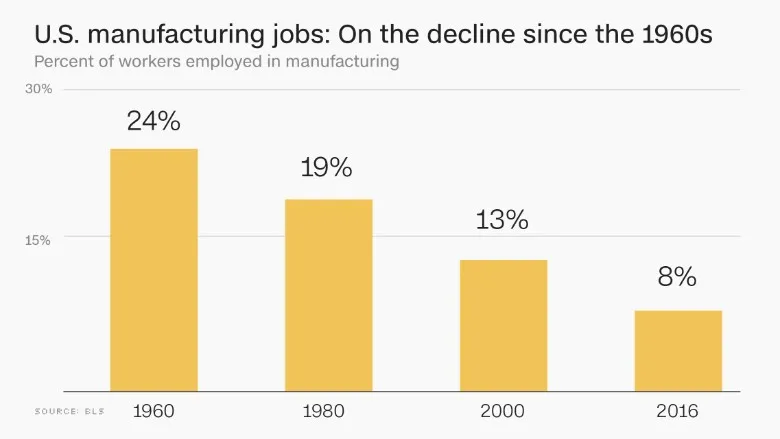

Roughly 40 million white American men grew up in the 50’s and 60’s when our manufacturing base produced two thirds of the world’s goods with less than 10% of the world’s population. In 1970 one of every four jobs in the country was in manufacturing. Factory workers bought houses and new cars, and sent their kids to college.

However, this boom-time economic dominance was a temporary distortion of normal economic competition. Our manufacturing base was bolstered by war production and completely intact. Europe and Asia were in ruins. So the way economics works, what followed over the next few decades was like water finding its level. Europe rebuilt. Japan rebuilt. World consumers had more choices. Our dominance naturally declined because of basic economics, not politics or policy.

Natural process, yes; and unavoidable; but it felt like decline. And it was famed and presented as decline. Google the phrase “decline of American manufacturing” and you get about four million hits.

Some other trends piled on. Some people in Serbia, Ukraine, Sri Lanka, Costa Rica and Vietnam can write computer code as well as some people in the U.S. There is a worldwide cottage industry of freelance SEO experts, copy editors, and personal assistants. People in India are happy to answer tech support and airline customer service calls for a lot less than most Americans would. Decline or not, natural or not, some jobs went away.

Then there’s also the impact of natural job evolution. In the past three decades, the number of jobs for knowledge workers has never been rising as quickly as it is right now. We had the personal computer boom, then the Internet boom, and then the mobile smart phone boom, social media, and lean energy. Better new jobs replace traditional jobs, but not for the same people. They go to new people somewhere else. Those same assembly-line white males who used to punch a time clock felt it most.

Second: To the Privileged, Equality Feels Like Persecution*

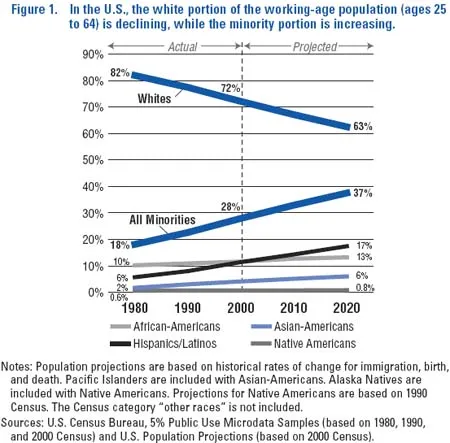

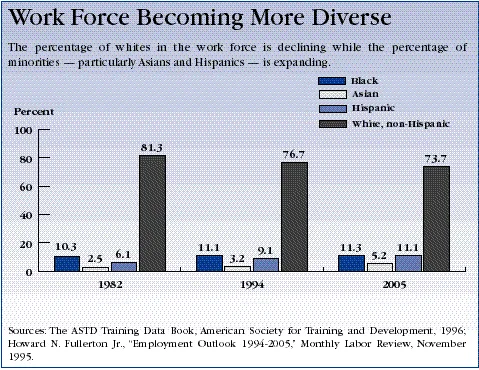

The post-war economic boom, however, was for not for all America; it was for straight white male America only. White women got to ride along in the bus, but mainly only as wives, secretaries, nurses, or teachers. And minorities had to sit in the back. Or outside looking in.

That inequality had to change. I can’t prove it, but I know it’s true. And if you don’t agree with me on that, stop reading this post and go away. Maybe it’s because of a fairness gene that struggles with the selfishness gene and the fear-of-otherness gene. Or maybe it was the power of decades of protest, civil rights movements, women’s lib movements, gay rights and trans movements. Maybe because of political leaders, thought leaders, media, movies, and television. Right and wrong evolves. Change happens. Equality dragged white male America, kicking and screaming or not, towards sharing.

Meanwhile the U.S. population has changed too. When the older whites look around, it looks like too many immigrants have jobs while they don’t. And they don’t see that the others might have been more qualified, willing to work harder, or in jobs nobody else wants. To the privileged, equality feels like persecution.

Nobody out of work wants to blame themselves; or economic change, or their lack of education, training and trainability. But they do want to blame somebody. So tens of millions blame the slow, halting, progress of the last few decades away from privilege and towards equality (not enough, of course; but at least some progress has been made). Which means they blame Blacks, Mexicans, women, Muslims, immigrants, gays, and so on.

Sarah Cooper found this quote in an Amazon review, and posted it in Suck it Up here on Medium:

There are scholarships for women, for blacks, for Hispanics, for everyone — EXCEPT white males. Even the professors hate white males. America will pay for this hatred. When we get a hold of power (political, business, financial, etc.) we will remember the way we were treated.

And there it is. An American white male writing “when we get a hold of power” with a straight face, as if from the outside looking in.

Third: Celebrity Replaces Substance

Paris Hilton. Kim Kardashian. Pop stars, sports stars. For decades now we slowly but steadily replaced substance with celebrity. Respect is a matter of mentions more than accomplishments. Google Justin Bieber and you get 55 million hits. Google John Kasich and you get 650 thousand.

This isn’t new. California elected movie song-and-dance star George Murphy to the senate in 1965 and movie star Ronald Reagan as governor in 1966.

But it is getting steadily stronger and more obvious. Celebrity is power. Celebrity becomes attention, and attention is the ultimate goal. Face recognition is power. Television appearances generate power. Voter and viewers care way more about celebrity gossip than politics.

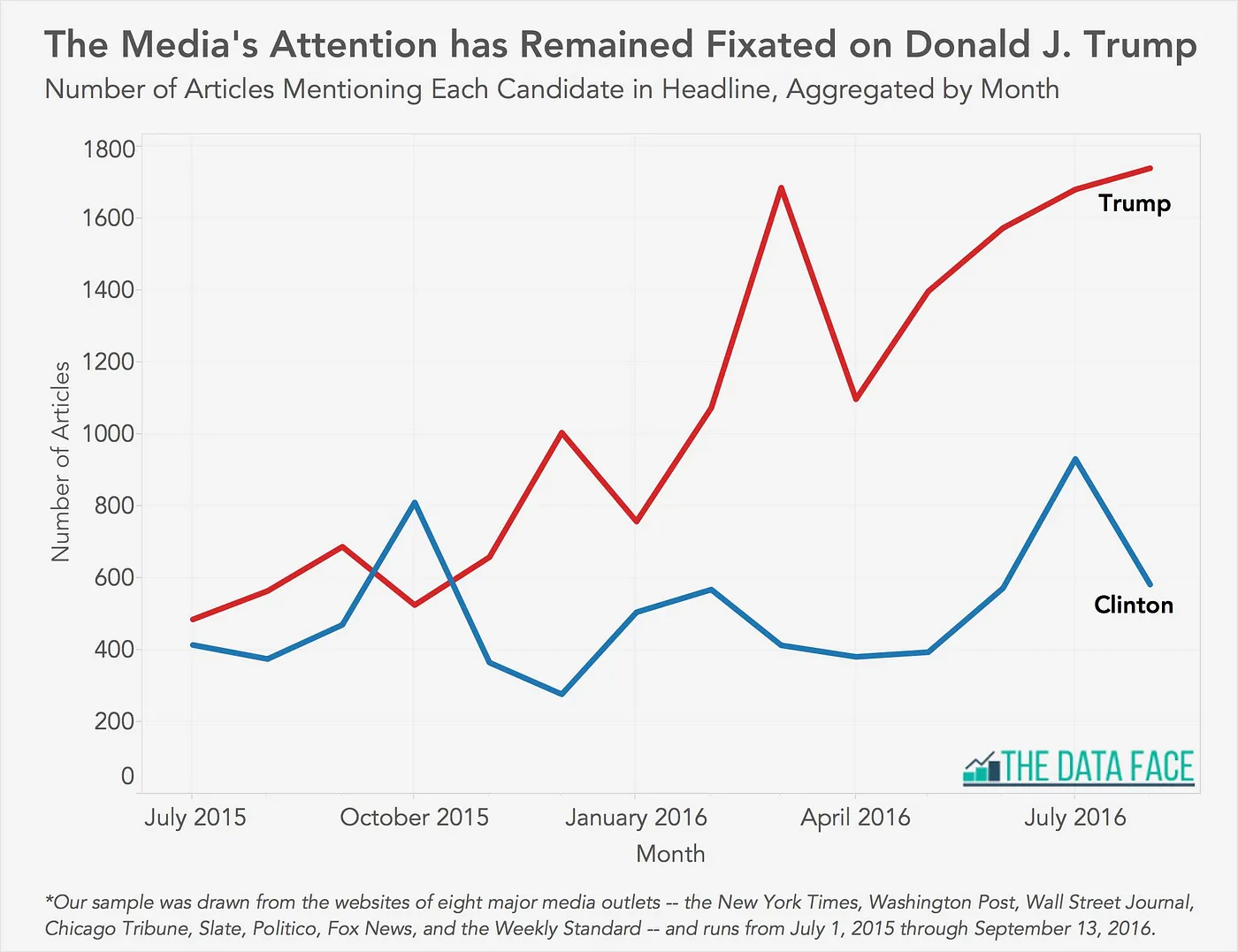

The FCC equal time rule used to matter. Networks couldn’t put one candidate on the air without giving equal time to the other. But then news reports are an exception, celebrity is news, so equal time meant nothing when a celebrity reality TV star ran for president against a career politician.

Fourth: Meritocracy, Excellent, and Elitism

We are no longer a country that educates its people. Sure, education still correlates roughly with employment. But we are not like we were for about a generation, after the Russians beat us to space with Sputnik in 1957. But then we got into tax revolt, and mistaking the lowest common denominator for equality in education. We objected to discipline in schools, kids flunking grades, and accelerated classes. We show up with the also-rans in global surveys of education and academic achievement. In 2015 academic surveys, the U.S. ranks 38th in math, 24th in science, and 23rd in reading.

Excellence got confused with elitism, and elite became a bad word. When I was a kid, the honor roll was prestigious. Getting into an Ivy League school made somebody smart, not an effete Eastern liberal. Intellectuals like William F. Buckley were listened to and admired, even by liberals. Now the good students are nerds, and conservatives listen to Rush Limbaugh and Alex Jones. And we admire super heroes and celebrities.

Millions of voters apparently want to look down, or sideways, but not up to their politicians. They want somebody “like us.” Analysts agreed that Bush beat Gore over who to have a beer with, not who was smarter. Urban, ivy-league-educated politicians speak in fake drawls and talk about “folks.” We don’t want somebody smarter than we are.

Fifth: Truth by Quantity Instead of Quality

Back in the 1960s public opinion fought over facts. We all watched the network news on the three main networks, and we read the local newspaper, and we chose Time or Newsweek. Facts like the real death toll and real lack of progress turned public opinion over the Vietnam War. Video images of beatings and brutality changed public opinion over the Civil Rights movement.

In the background, the main news media had to stay in the center to keep their audience. There was no money in fringes. So we had Huntley and Brinkley, Walter Cronkite, and Dan Rather looking for facts, jumping from right to left or Republican to Democrat as the facts came up. Truth, as evaluated by evidence, was good business. It got the largest audiences.

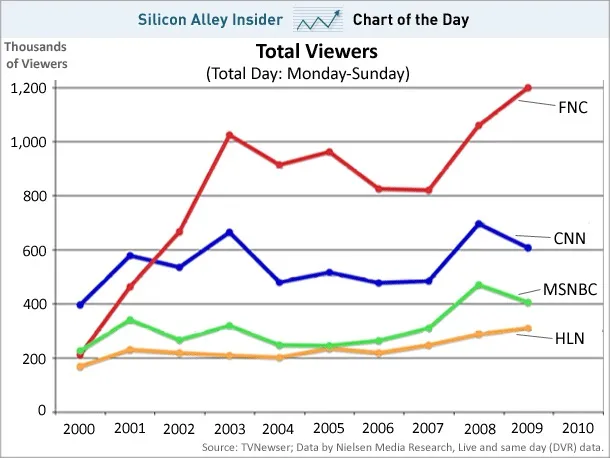

Then Roger Ailes and Fox News made money by appealing to a tribe. It was us vs. them. The common enemy. The spin. Fox News watchers grew steadily more loyal and less connected to the rest of the country. And the network prospered. Forget the whole public, appeal to an interest group. Bring in the Republican Party. Bring in right-wing Christian Evangelism. Dive truth into us vs. them. Replace truth with much-repeated lies. And it works commercially.

Republicans caught on. Democrats didn’t. Republicans organized around talking points that they all repeated, with straight face. They were organized, efficient, and powerful. Democrats remained diverse and confused. So the talking points won. And republicans won.

Social media reinforced truth by quantity rather than quality. Who needs editors? Who needs evidence? Find truth in Facebook likes and retweets, true or not. Facebook and search engine algorithms determine who sees what. They sort and select and end up reinforcing the confusion between truth and organized, coordinated, repeated lies. Which creates a populace particularly vulnerable to bots, hackers, and bubbles.

All of Which Brings us To Donald Trump as President

So there it is. Donald Trump as president. I thought this couldn’t have happened, until it did. And it shouldn’t have happened, but it did. So I try to understand. And identifying the underlying trends helps.

* That quote “to the privileged, equality feels like persecution” is not my own. I picked it up in a comment on Medium by Dan Ray, on Sarah Cooper’s post Suck it Up.