Category: 4. Seventies

Protected: 1970: Crazy Married

1970: A Quick Change in Direction

I didn’t just fall in love with journalism. I also fell out of love with literature. Well, the graduate level study of literature.

We’d moved to Eugene in September of 1970, just nine months married, for me to do a PhD track in Comparative Literature. I loved English Lit, but had lots of German Lit too after a year in Innsbruck, and then I’d fallen in love with Vange and learned Spanish. We were in Eugene because the University of Oregon had one of the better comparative literature programs on the west coast, second to Stanford (which hadn’t accepted me). They didn’t give me money, but they admitted me.

Two weeks into my supposed PhD lit courses, I found myself having to do a 10-page paper on Robert Herrick’s poem ‘The Altar’, notable for how its written form looked like an altar (long lines, short lines, long lines). In other words, boring, meaningless drilling down into the detail. 10 pages of it.

Meanwhile we’d just bought me a pair of shoes from a store clerk who brightened up, while helping me try on shoes, because he too had studied literature, and had the PhD. So I wanted out. But we’d moved to Eugene, moved into housing, paid tuition, taken a loan.

I spent an evening browsing the university catalog. The next morning I walked into the school of Journalism and waited until I could talk to the dean. As it turned out, he too had gone from PhD studies in Literature to Journalism. I switched that day. And Dean John Crawford found me scholarship money and helped me every way he could. And damn, what a difference! Journalism also cared about writing, but it was also living, changing the world, doing something that meant something. I found my home there and dove in. I did two years worth of class work in nine months, with straight As. I ended up getting the degree with honors, but that was four years later, after I’d finally done a thesis.

The switch was complete. I was very glad to identify as journalist, not poet, and much less lit professor.

1971: Getting a Job in Journalism

June of 1971. We lived in the old Amazon married student housing that has long since been plowed over. It was a collection of old army barracks, left over from the second world war, with some two-story apartment buildings and a row of single story wooden houses, with curved roofs dating back to military use, which is where we lived. It covered several acres just east of South Eugene High School, west of East Patterson, north of 24th. Ave, across the street from the old YMCA.

Often on weekdays around noon I’d start popping out of the front door to look north along the row of identical houses, anxious for the mailman. When I did, I’d often see others doing the same. Our little house was one of the closest to the south end of the row of about 12 or maybe 14 little houses. The mailman would come from the opposite end of the row, walking, and leave the mail door by door. As I opened the door and looked out, I’d often see other people doing the same. Like prairie dogs in a Disney documentary.

Jobs were scarce in 1971. And jobs are always scarce for grad students looking for their first jobs. Of course there are other reasons to look for the mail, and not all of us were done like I was then, and looking for jobs. But it felt like that to me.

We were broke. And we were ready to leave Eugene and the University of Oregon and get into real life. I hadn’t finished my master’s in Journalism, but I’d finished the class work so all I needed was to do a thesis, which I could do from anywhere. We’d used up the $5,000 student loan and Vange’s meager earnings at the university weren’t enough. We needed to either get a real job or get another student loan.

I really wanted a real job in real journalism. I’d fallen thoroughly in love with the idea of it. My grad classes in Journalism were steeped in the lore, the traditions, the ethic, the meaning of it all. The great newspapers, the reporters, the scoops, the think pieces and investigative pieces, I wanted all of it. I’d sent resumes and applications all over Oregon, California, and Mexico City. Each of them was to me like a lottery ticket, a reason to hope, a reason to wait anxiously for the mail to arrive.

I’d not only fallen in love with Journalism; I’d also fallen into it. Literally. We’d moved to Eugene in September of 1970, just nine months married, for me to do a PhD track in Comparative Literature. I loved English Lit, but had lots of German Lit too aftr a year in Innsbruck, and then I’d fallen in love with Vange and learned Spanish. The University of Oregon had one of the better comparative literature programs on the west coast, second to Stanford (which hadn’t accepted me). They didn’t give me money, but they admitted me. Two weeks into that, I found myself having to do a 10-page paper on Robert Herrick’s poem ‘The Altar’, notable for how its written form looked like an altar (long lines, short lines, long lines). In other words, boring, meaningless drilling down into the detail. Meanwhile we’d just bought me a pair of shoes from a store clerk who brightened up, while helping me try on shoes, because he too had studied literature, and had the PhD. So I wanted out. But we’d moved to Eugene, moved into housing, paid tuition, taken a loan. I spent an evening browsing the university catalog. The next morning I walked into the school of Journalism and waited until I could talk to the dean. As it turned out, he too had gone from PhD studies in Literature to Journalism. I switched that day. And Dean John Crawford found me scholarship money and helped me every way he could. And damn, what a difference! Journalism also cared about writing, but it was also living, changing the world, doing something that meant something. I found my home there and dove in, doing two years of class work in nine months, with straight As (I ended up getting the degree with honors, but that was four years later, after I’d finally done a thesis).

Mexico City was a variation on the dream. Vange’s mom Eva connected us to a University of Oregon alum in Mexico City with a head-hunter business, and with his encouragement we allowed ourselves to dream the life of a foreign correspondent, with a lavish salary, company car, private school tuition for kids (not that we had any at that point). It turned out to be horribly unrealistic, by the way — but it fueled the dream.

By the time the envelope from the ‘Mexico City News’ came, I’d interviewed at AP in Portland (they’d said “not enough professional experience,” which was hard to argue, since I had none). And again at a weekly in Newport, Oregon (same story: only hiring experienced journalists).

The envelope was thicker than most. I opened it eagerly. And, to my amazement, it contained plane tickets! Back then plane tickets came as a booklet of several pages, with copies for boarding and so on, and a cardboard back, all of it sized to fit nicely in a standard letter envelope. The flights were ‘open’ so I could call and reserve. Mexico City and back, paid for by the News.

We were amazed, excited, deliriously happy. At that moment, we were living proof of the idea that real happiness is anticipation of happiness. There was the still-alive dream of the foreign correspondent living in luxury in a foreign capital. And for Vange, she was 23 years old, missed her mom and her siblings and life in Mexico City, and this meant going back there was married to her American husband. For me, also 23, this was not just the ticket to real actual Journalism, but also a ticket to move again (after the year in Innsbruck) away from the United States to another country, to live and work there. And to Mexico City, my wife’s home town, which I’d really liked in our visits.

So I went to Mexico City. Vange waited at home because it was an expensive round trip. Her mom Eva met me at the airport and treated me royally along with Laura her sister and Horacio her brother. We had a nice dinner that night, and a lot of encouragement. My Spanish had improved with each visit, and I’d gone from my first-year Spanish at Notre Dame to a Eva loaned me her car for the three day visit. And Vange waited with very little news, because back then, calls from Mexico City to Oregon were prohibitively expensive, like $20 per minute.

The next day, reality hit the dream. enjoyed driving Eva’s little Datsun bluebird through city traffic. I found a parking space, which was still possible in 1971. But then I arrived at the Novedades building.

The ‘Novedades’ was one of at least six daily newspapers in Mexico City. It was not the best (Excelsior), but it was a major player. ‘The Mexico City News,’ the only English-language newspaper in the city, was a Novedades property.

The Novedades building was on Avenida Morelos, near the corner of Balderas, in the heart of the newspaper district. Newspapers clustered together, within one or two blocks of each other, in downtown Mexico between Reforma and the old downtown district around the Cathedral and National Palace. The ornate but aged dark stone building was probably built in the 1920s, I guessed. It was six floors high, run down, but still working hard every day, the brain of a national network of newspapers and magazines.

‘The News’ newsroom included maybe eight desks, a water cooler, and a 10 by 20 editor’s office with a door and windows out to the desks. It was on the fourth floor. The editor, Jaime Plenn, was a small older bald man with a slight New York accent and no gift for small talk. He made no effort to hide his discomfort with what I discovered was me having been pushed on him by a then-vague power called “upstairs.” Somebody (he rolled his eyes as he said it) seemed to think that a Mexican wife and a grad degree made a journalist. That same somebody (eyes rolling again) thought they could build a new generation of news people for the news, people who weren’t nondescript oddballs and misfits.

And oddballs and misfits they were. Stereotypes as if from a bad situation comedy. The sportswriter had a foul mouth and the beer belly. The business editor was a fifty-something portly woman with short hair and a cloud of cigar smoke. The social editor was a well dressed late-thirties woman who seemed like she’d ridden a couple of decades on being good looking (and she still was). The main reporter came with a New York accent, a big sweeping mustache, long hair, a flower shirt and sandals.

I “interviewed” with all of them. All were generally welcoming to this 23-year-old American kid who looked like he was 17. They were mostly showing off, trying to play their character roles. Jaime Plenn made it clear, from the beginning, that the job was mine to take.

The dream crashed and burned when I got to the salary. The job was mine to take. The salary was $MN3,200 pesos per month. That translated to $267 per month. I took that with a straight face because I’d never actually lived in Mexico City; but it seemed like very little. And thus ended day one of the job visit. I was supposed to come back the following day to sign papers, and then to get my ass down to Mexico City as soon as I could.

Eva was shocked. “That’s impossible. You can’t live with that,” she said. She was so disappointed. She too had bought into the dream of the foreign correspondent, fed by her friend Craig Dudley, the University of Oregon alum. Craig, as it turned out, dealt with expat executives from major corporations. He had no idea how journalists lived. Eva had bought into the dream too.

That evening, as I sat at dinner with Eva, Laura, and Horacio at dinner, they were all shocked. Eva, who ached to have Vange back again in Mexico City, led the charge. She didn’t want me to make a mistake. She was never able to give bad advice on purpose.

“Tim, you have to tell them no. Go back tomorrow and tell them you can’t live on that.” She knew that I didn’t know costs and money in Mexico City. I hated to do what she said, because I had no job at all, I too wanted to move to Mexico City, and it was actual journalism. But I trusted Eva. I longed to talk to Vange about it, but I couldn’t, because we were that broke. And Eva clearly spoke for Vange too.

And so I did. I went back and told Jaime Plenn I wasn’t taking the job. Too little money. Which was a hard moment at first, and then an awkward moment, and then, as I sat and listened to a couple of calls, it became an appointment “upstairs.”

“Upstairs,” as it turned out, was the office of Guillermo Gutierrez, a wealthy Bolivian expat political exile, with a big desk in a big office of dark oak and deep green, and a secretary in an outer office. On the fifth floor. I didn’t know his history or even his position in the Novedades organization. To me he was a Mexican businessman dressed in an expensive business shirt, tie, and suspenders, with his suit coat on a rack. He was also very clearly the author of the idea of getting this young American with Journalism education and Mexican wife down to the Mexico City News. Upping the quality was his idea.

“Here’s what we’re going to do,” Guillermo Gutierrez said, leaning forward towards me, elbows on the desk, speaking softly. “You take the job for the 3,200 pesos. Take the paycheck along with everybody else on the fourth floor. But once a month, you come upstairs to my office, and I’ll hand you 5,000 more pesos in cash. And that will remain between you and me.”

So, victory snatched from the jaws of defeat. I said yes. The dream, downgraded from good money and luxury lifestyle to barely enough, survived. I called Vange to tell her, in three minutes, I’d taken the job and we were moving to Mexico City. I finished the details and flew home to a very happy young wife and eager anticipation. We packed up the 1968 Volkswagen I’d bought in Munich. We drove once again down to Mexico City, our second time, but this time to stay. Our nine years in Mexico City began.

However, the story doesn’t end there. The plot actually thickened. For several months I worked at The News, starting on the copy desk, doing cuts and edits and writing headlines, and then getting to go out and do reporting on stories. It was journalism, quirky or not. I liked my oddball coworkers and even Jaime warmed up a lot.

But then one day in November when I went upstairs for my monthly under-the-table payoff from Guillermo Gutierrez,he was gone. Gone for good, his secretary told me. Ya se fue para siempre. That’s when I learned he had been a political refugee from Bolivia, which meant nothing to me until then. Hugo Banzer had taken over Bolivia via military coup, and Gutierrez, a right-winger, had gone back to Bolivia to join the Banzer government. And that was that. Nobody knew (or admitted to knowing) about my arrangement, which had always been secret. He’d made me promise never to tell Jaime Plenn or coworkers, and I kept that promise. So I was stuck, badly.

Two months later I joined UPI, United Press International, as night editor for Mexico City. Full time. Paid in dollars via deposit into Citibank in New York, for $115 a week.

That’s me in 1972 in the UPI office at Avenida Morelos 110, in Mexico City.

1972: Get the Story or Don’t Come Back

June, 1972. I had turned 24. Vange was due with Laura, our first, in a month. I’d been Night Editor, Mexico City, fox six months. Denny Davis, the Mexico City bureau chief, decided to send me to cover the anniversary of the San Cosme riots of June 10, 1971. Also called El Halconazo, the Corpus Christi Riots … which were depicted in the 2018 Alfonso Cuaron oscar-winning film, Roma.

Denny was hard for me to like. He was a former military man, middle forties, dark brown hair with a brush cut, straight laced, impersonal. A dedicated journalist, though. He believed in the tradition and the value of what we were doing. Looking back from decades later, his off-putting manner may have been shyness. And an odd factor in a boss-underling relationship, for the setting of UPI in Mexico City, is that my Spanish was fluent and I was totally integrated into my Mexican family. Denny always sounded, looked, and acted like an outsider.

What he said, though, has stuck with me for life:

“You’re mainstream now. This is real journalism. It’s not ‘do it or have a good reason why not.’ It’s ‘do it or don’t come back.

“Go a day early if you want, check out the area, give somebody with a second floor apartment and a phone a hundred pesos in advance, and another hundred on the day, to let you watch from the second story with a phone in your hand.

“Or do something else. I don’t care. But do understand that you can’t just have a reason why you didn’t get the story. Reasons why not don’t matter. If you don’t get the story, don’t come back. You’re fired.”

It turns out that during the real riot, in 1971, my predecessor, Paul Wyatt, was late with the story. He didn’t get fired mostly because he stumbled into the office late wearing a white dress shirt covered in blood. He wasn’t wounded but a student protestor standing next to him was shot dead. Paul was covering it from the ground, mixed with the crowd. That was obviously traumatic in the UPI bureau. Denny didn’t make it about him, but I’m pretty sure he didn’t want me dead. So he wanted his advice taken seriously.

This story here isn’t about my riots, or my news report, or what happened to me on June 10 of 1972. There was no story. The protest fizzled out quickly, without making anybody’s news. I did go a day early and scope a second-story apartment, and paid the occupant 100 pesos. I did go before the announced demonstration and get settled in my watching post. I did call in the story. But it was a non-story.

The actual history of the 1971 event is shown very well in the movie ‘Roma.’ The Mexican government turned to the fascist playbook back then, after the riots of 1968, and trained a paramilitary force of young men who wore khakis and white shirts. Those men attacked the rioters, right-wing disguising itself as left wing, killing about 140 demonstrators.

And the nugget here is not what happened, but the fallacy of equivalence: too many people think they can get away with not getting things done if they have a reason why not, instead. I don’t. Denny Davis taught me that lesson and it stuck.

1973-74: Around the World in 31 Days

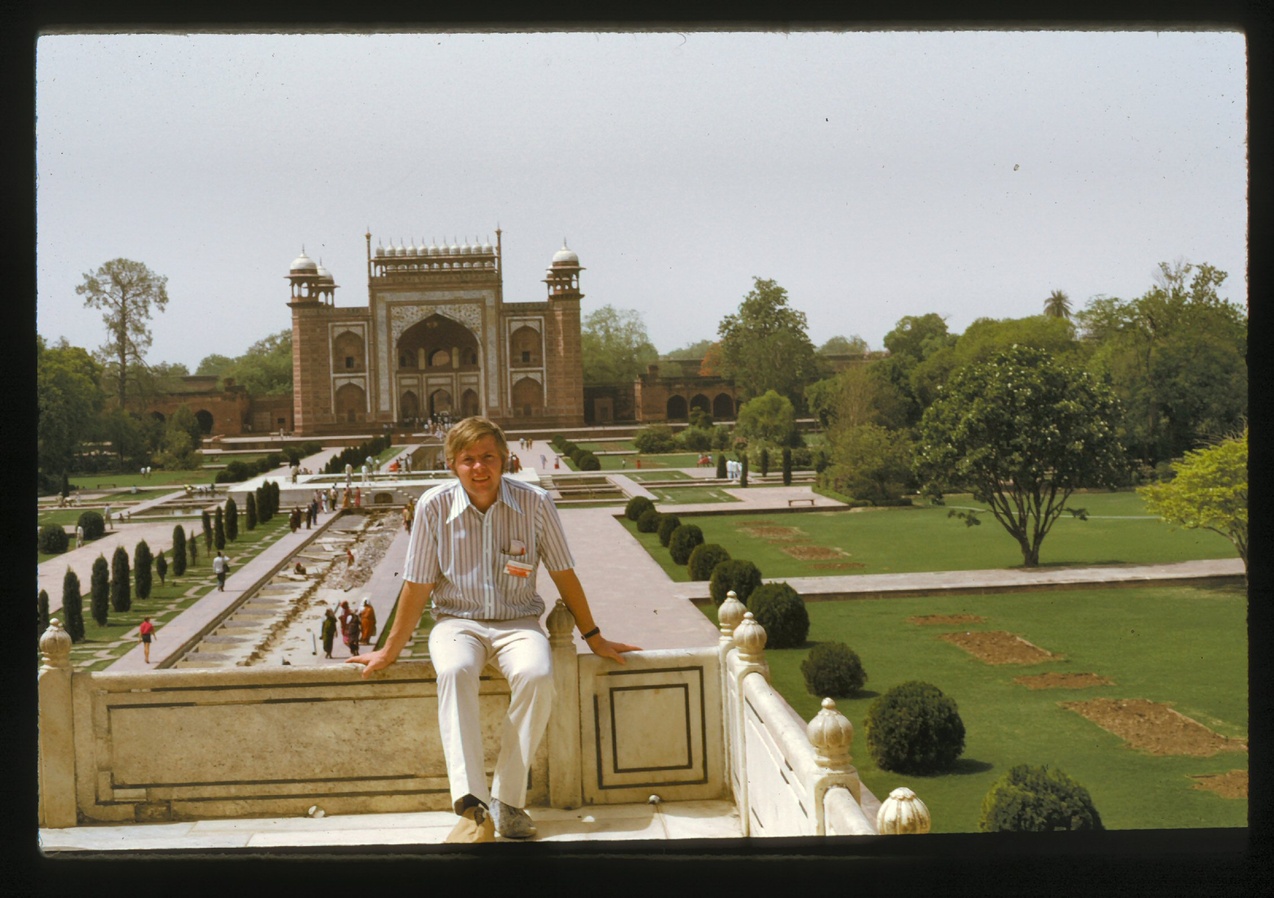

“Tim, can you get six weeks off, beginning next month? I want to send you around the world, as a tour guide for my next Orbis Nostrum group.” That was Raul, my brother-in-law, whose family business was Mexamerica, the largest Mexican-owned travel agency in the country. Raul had taken command from his father. It was in April of 1973. The Orbis Nostrum was Mexamerica’s high-end luxury tour around the world, going west from Mexico City to Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, Hong Kong, Bangkok, New Delhi, Agra, Teheran, Isfajan, Jerusalem, Athens, Paris, and from Paris to Mexico City. In 31 days. And it happened that United Press International, my employer in Mexico City, had six-day work weeks and six-week vacations; and I was due a six-week vacation.

“And I’m sorry,” Raul added, “but I can only pay you $1,000.” I was earning $115 a week at UPI. And Vange was pregnant with Sabrina, our second. And we had no health insurance.

I said yes. I was 25, living in Mexico City, leading a group of 68 wealthy Mexican tourists around the world in 31 days. And getting paid to do it. And Vange, who could have objected, was all in favor. “Do it. What an opportunity.”

Three weeks later I met the group in a fancy meeting room in the Maria Isabel Sheraton, overlooking the Angel of Independence on Reforma, the Thursday before our Tuesday departure. I was buoyed by about two hours of Raul’s pre-trip training. For example, “tell them to bring strong luggage. Tell them the airlines butcher your luggage, so get new suitcases.” That, so they wouldn’t complain to me about damaged luggage, because I’d warned them. Also, “when in doubt, lie. Don’t ever let on you haven’t been there before. You have the local guides with you to help. Wing it.”

For the group of 68 I had two co-tour-guides, my mother-in-law Eva, and a pretty and amiable young woman from Mexamerica, Antonieta. The group split into two after Bangkok, with Eva and Antonieta taking 38 of them through Singapore and Hawaii and then back to Mexico City. I took 30 of them on to India and the rest of the round-the-world tour. If you haven’t read anything else I’ve written about her, you should know that Eva was a wonderful person, warm, always happy, and a delight to travel with. Our relationship was not like normal in-laws. We really liked and appreciated each other, always.

Japan

It started with a really long flight. Back in 1973, commercial airliners couldn’t get from Mexico City all the way to Tokyo. We took a Japan Air Lines flight, with great service, that had to stop in Anchorage AL to refuel. And then, Tokyo, Hotel Imperial, terrible jet lag and me up at 4 in the morning — it was already daylight outside — and I walked for miles around the heart of Tokyo before breakfast. That first day was one of the longest of my life. I’ve never had worse jet lag and never been so tired. But we loaded the bus at 9 am for the tour of the city, which I stumbled through like a zombie. Thank goodness the local guides did everything, and spoke Spanish too, so I didn’t have to translate. We visited markets, and temples with beautiful gardens. And stores. We had a meal in a market. Our tour guides, thoughtful as they were, went off the city tour agenda to accommodate my tourists who wanted to look at Japanese pearls and jewelry. I was surprised how nice they were about it, given their packed city tour. They helped the driver park the bus and everything. In my jet lagged stupor, I bought some pearls for Vange, who I missed terribly.

The day ended, finally, at about nine pm, after a long boring dinner with women in kimonos and what felt like 40 hours of endless Kabuki theater, all of which had me struggling extremely hard to not fall asleep.

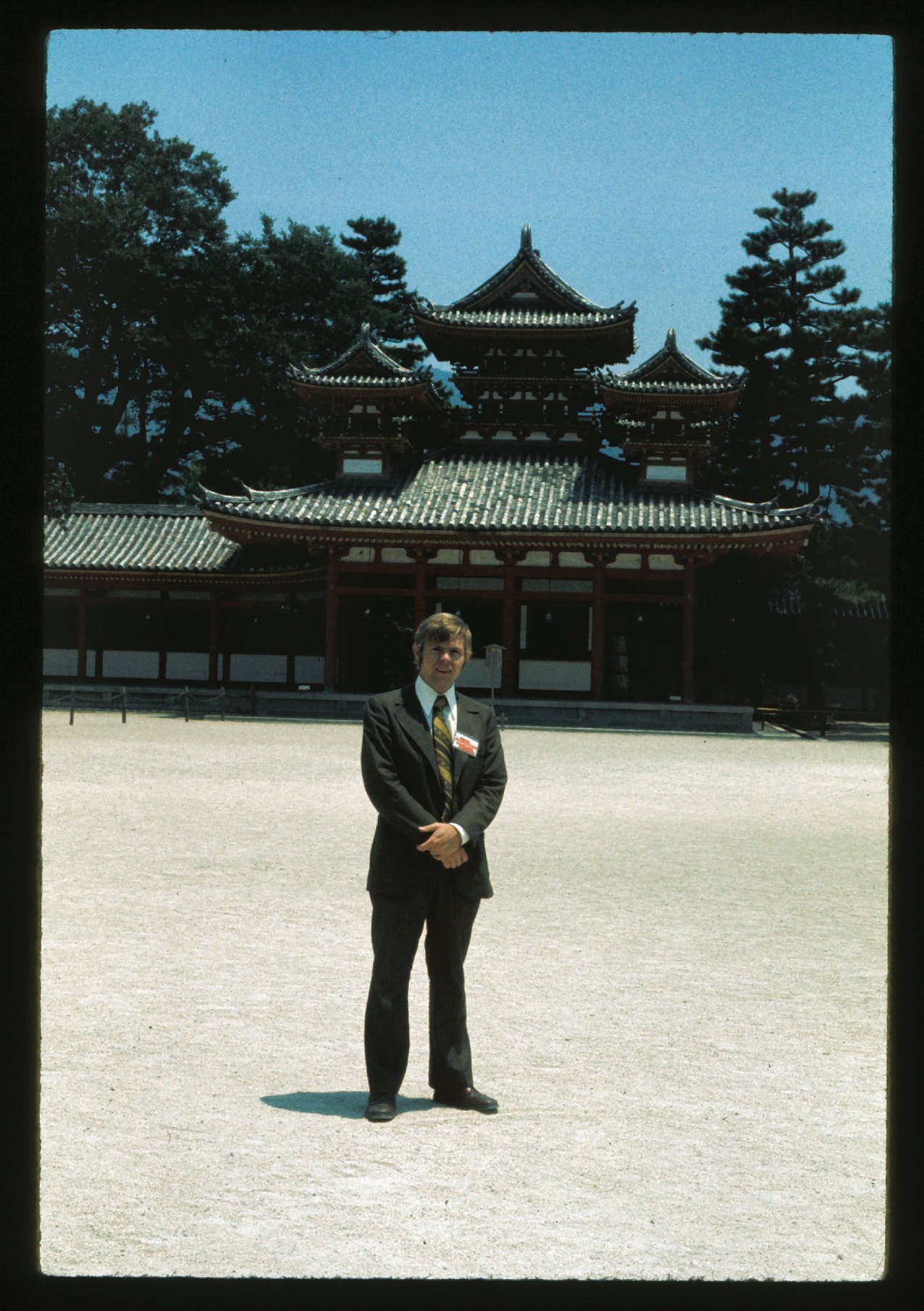

I dressed for that first day. Does the jet lag show?

I got to the hotel, asked at the desk for my key, and picked up two envelopes that seemed stuffed with paper. Thank God I was alone at that point, not in a group. I stuffed the envelopes into my day bag and dragged myself into my luxury hotel room. The envelopes contained hundreds of dollars worth of Japanese Yen, in cash. They came from the two stores our tour guides had visited. And that’s where I learned about tour guide commissions in stores. Raul had failed to tell me in advance. “I wanted you to start out innocent,” he told me later. “Tour guides can get too greedy. I wanted it to be a surprise.”

And that’s how, as it turned out, that Orbis Nostrum trip was not only a great adventure; it also paid for Sabrina’s birth, a great Pentax Reflex camera, two tailor made Hong Kong suits, and a lot of jewelry and other gifts for Vange. The $1,000 that Raul paid me turned out to be just the first of two or three thousand dollars I made that month. The Japanese tour guides, long-time associates with Raul and Mexamerica, filled me in about commissions during the next couple of days. They were getting 10% and so were we, they told me. And at that rate, my tourists were paying not a single extra Yen. The stores were happy to offer normal pricing and pay 20% off the top because the buses were like gold to them, tourists in a hurry trusting in great values, and anxious to spend. In Japan, they told me, everybody stuck with the standard 10%. “But that’s not how it goes everywhere,” my Japanese colleague told me. “In most countries they’ll give you more if you ask for more, and add the difference to what your tourists pay in prices.”

Japan, to a California kid looking for exotic Asia, was a let-down. Despite the occasional costumes, the temples, and the dinner shows, it was modern.

I took this picture at dawn the first day, looking back from a Hibiya Park towards the Imperial Palace, our hotel.

That first morning, at dawn, my walk included the gates of the Imperial gardens.

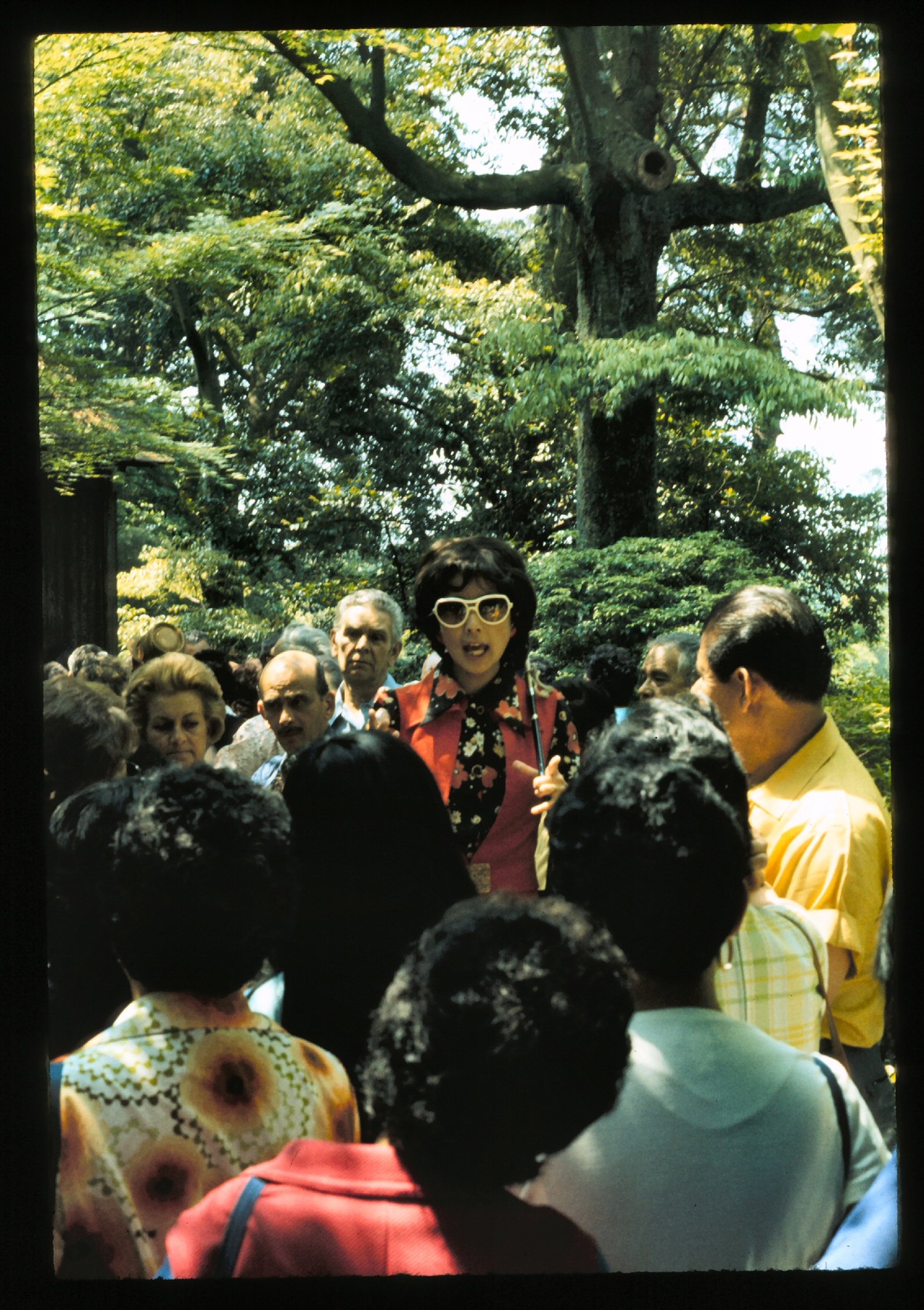

She was one of our two Spanish-speaking tour guides in Japan. With my group around her listening.

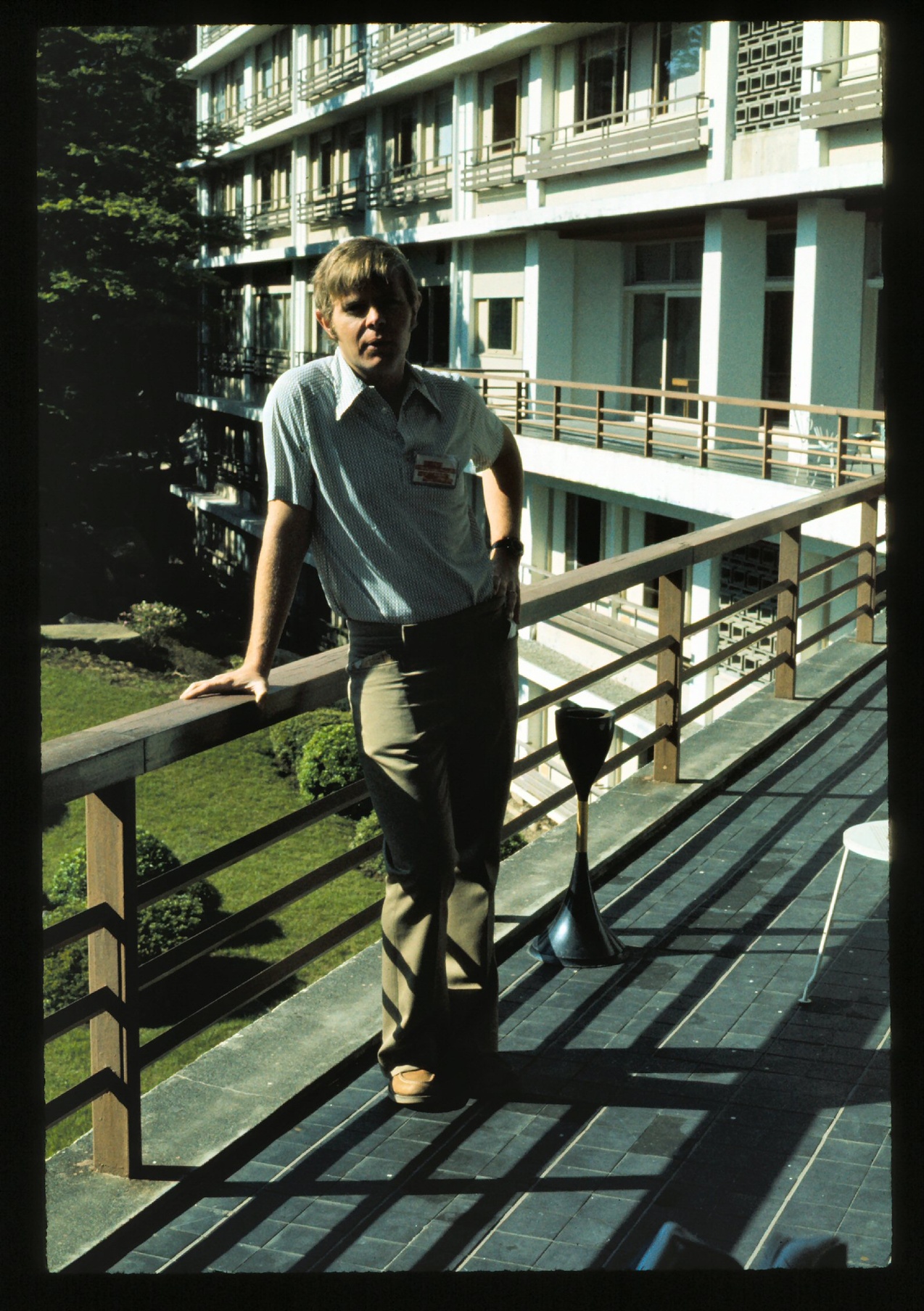

This was from the balcony of a hotel outside of Tokyo, close to Mt. Fuji.

One of many temples.

A random street scene in Tokyo

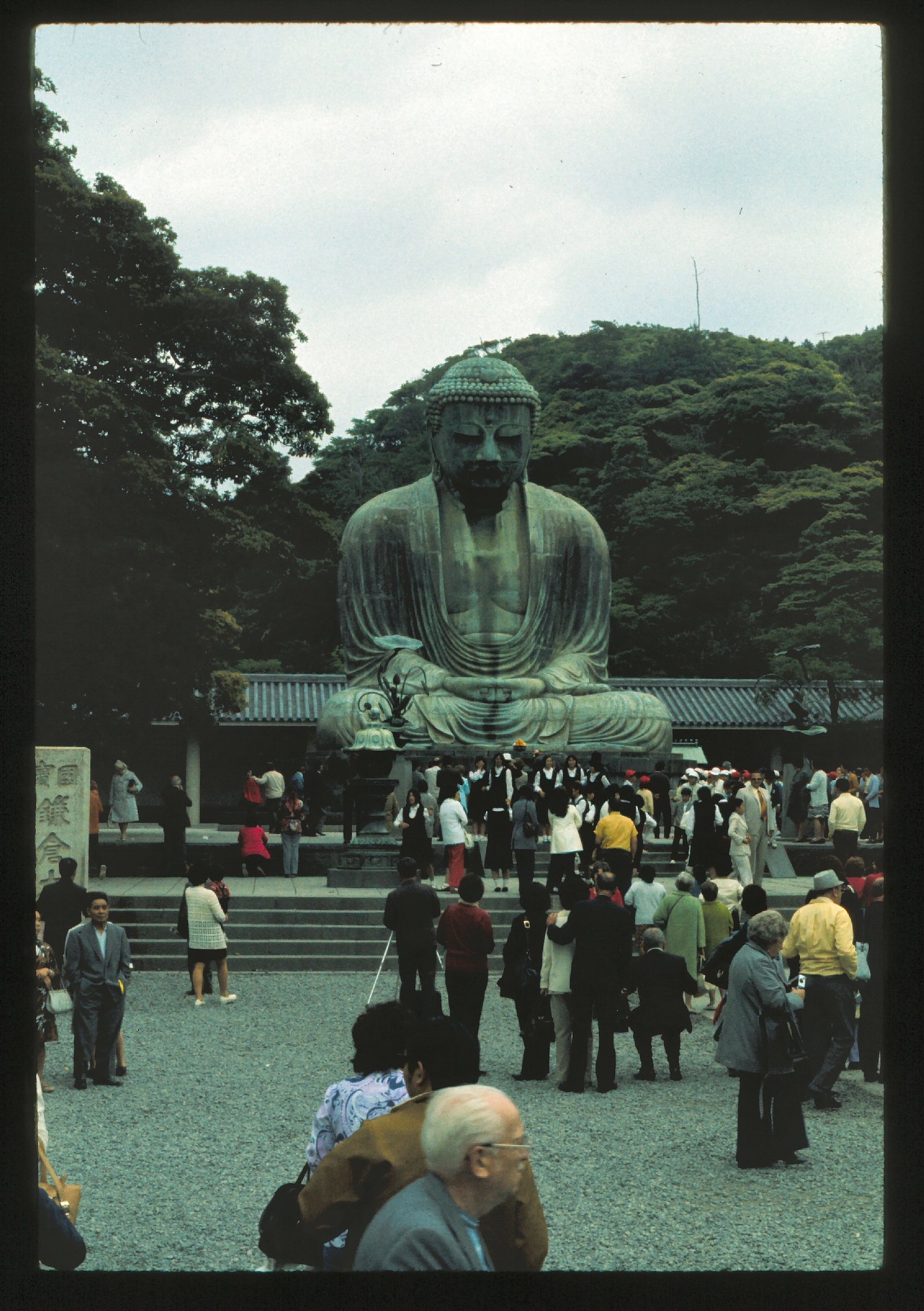

And a shrine to Buddha, outside of Tokyo.

Hong Kong

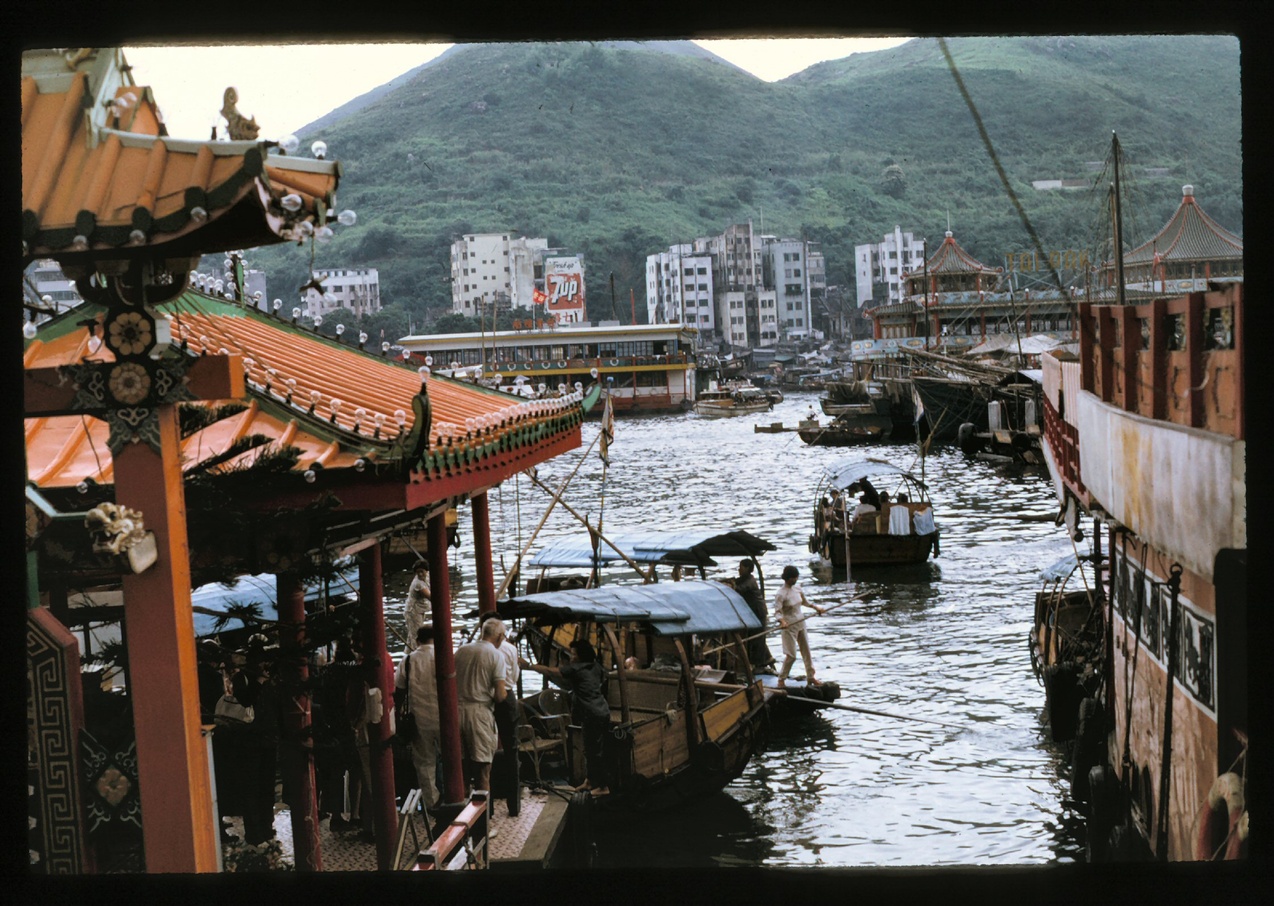

Hong Kong, however, was, well, the teeming streets, the exotic smells, a forest of neon signs blazing over narrow streets, the Star Ferry back in forth through the harbor to Kowloon, very tall buildings and steamy hot moisture-laden air, a woman smoking a cigarette in a marina full of old Chinese boats, floating restaurants, Asia as I had always imagined it, but better.

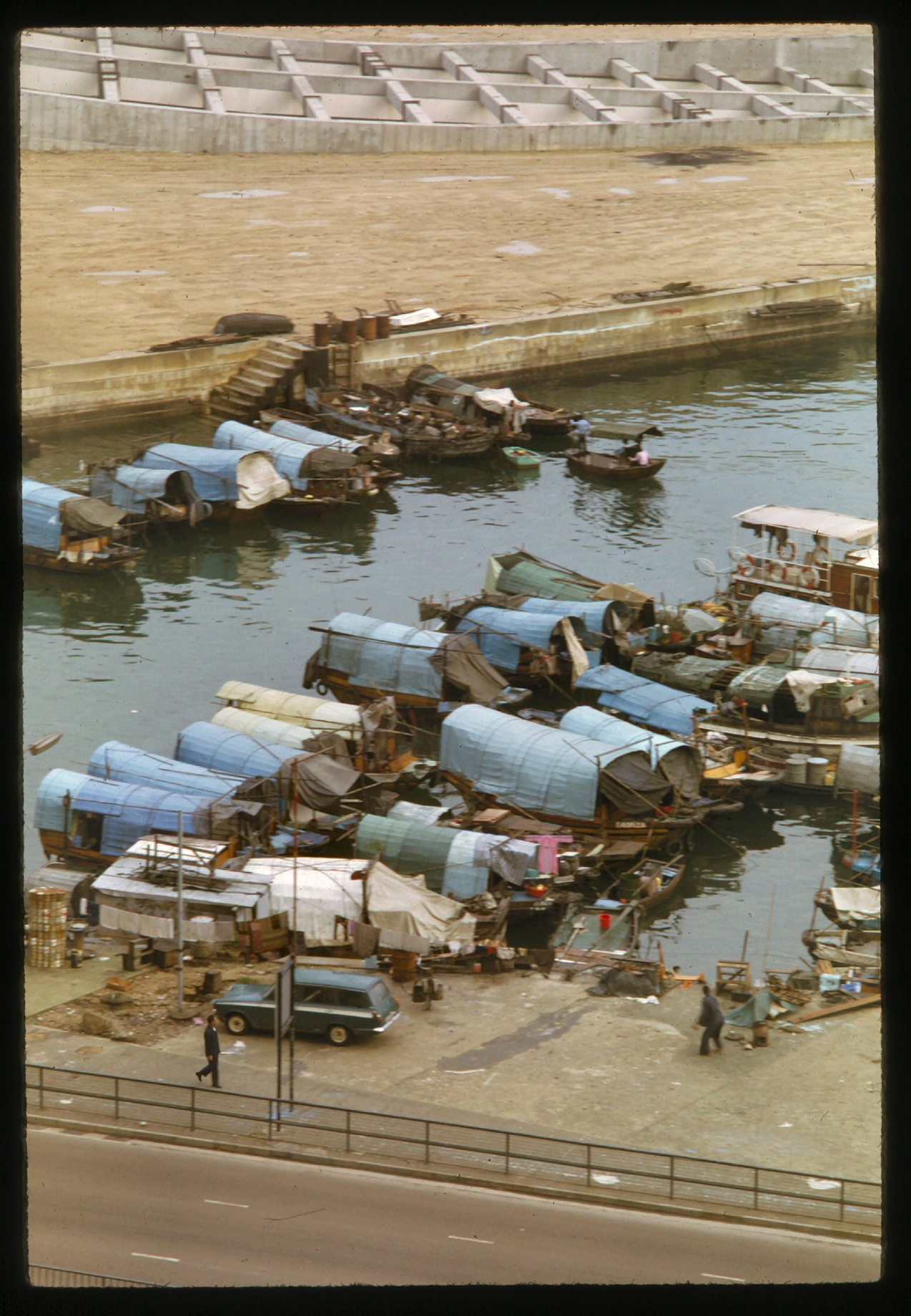

Aberdeen, Hong Kong

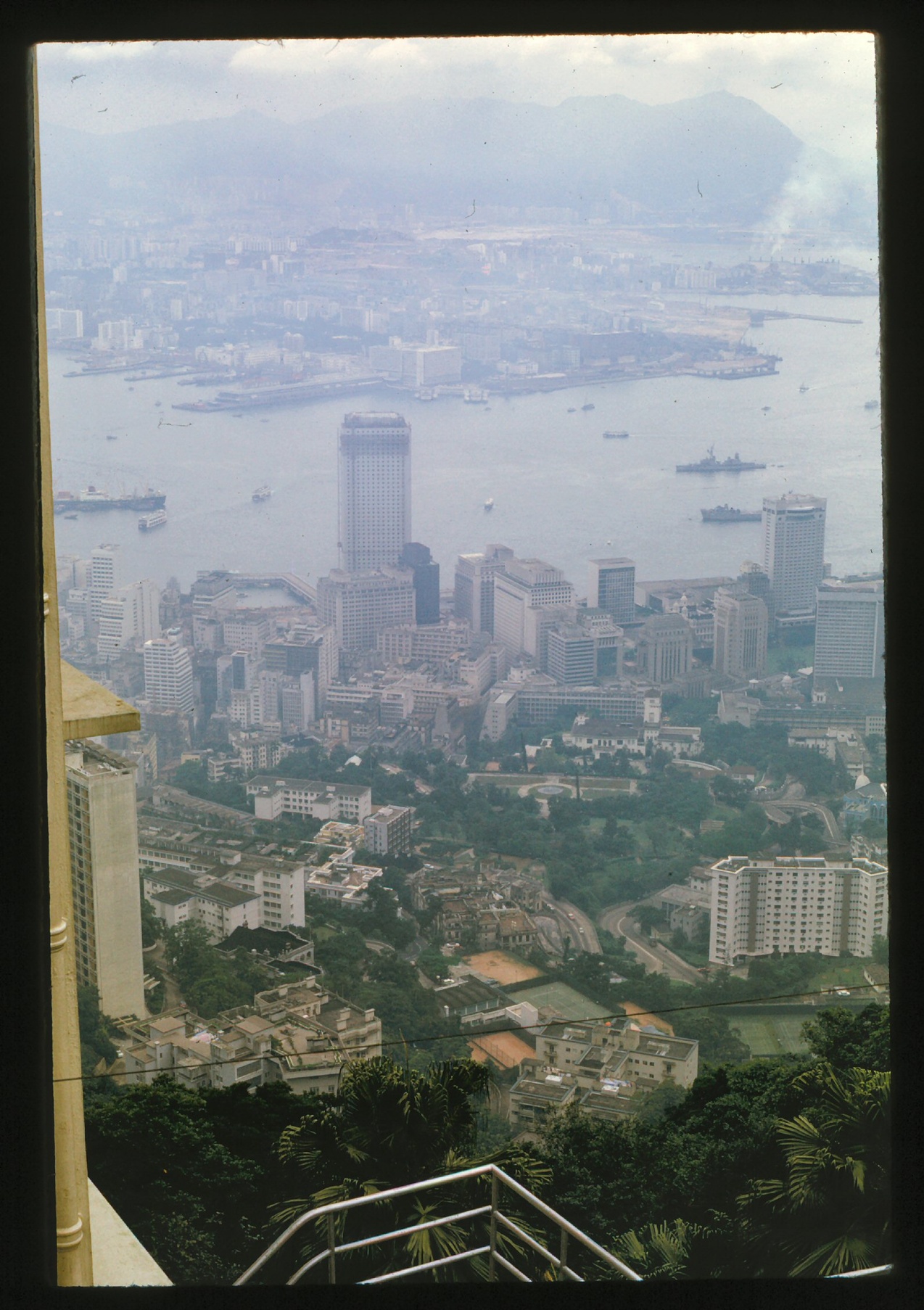

A view from Kowloon back at Hong Kong

Hong Kong. From my hotel room.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

The tour guide shuffle.

Much of the tour was predictable: tour bus times, city tours, monuments and temples, managed mealtimes, and store visits, always the store visits. Dinner theater of the worst kind, all of it supposedly typical and drenched in stereotypes. Chinese acrobats, Thai dancers in ancient costumes. Indian ceremonies. They faded into each other. I wondered if there was a tour group on the planes with us, changing costumes.

Bangkok

Another crowded third-world city, full of traffic. It struck me as a lot like Mexico City. And more buses, and more city tour, and more costumed folkloric dancing.

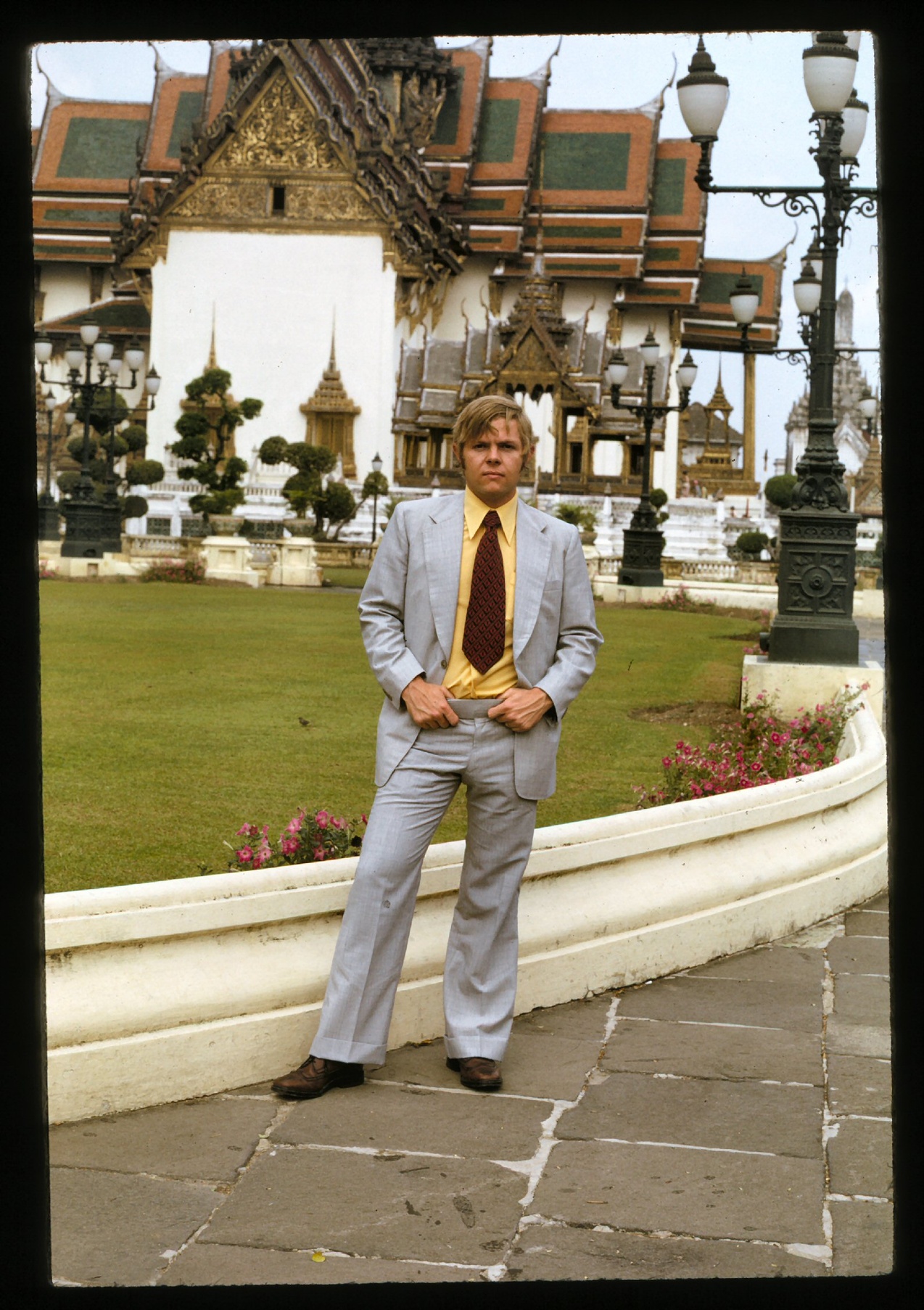

The royal palace in Bangkok showed the odd mix of millennia tradition with aspirations of 19th century Europe, as in the musical and movie ‘The King and I.’

And this picture from the Bangkok royal palace is about me showing off my brand-new Honk Kong suit. Really comfortable very light fine cloth, and of course, bell-bottom pants. It was, after all, 1973. My hair was not particularly long, for me; I’d had a hair cut before we left.

India

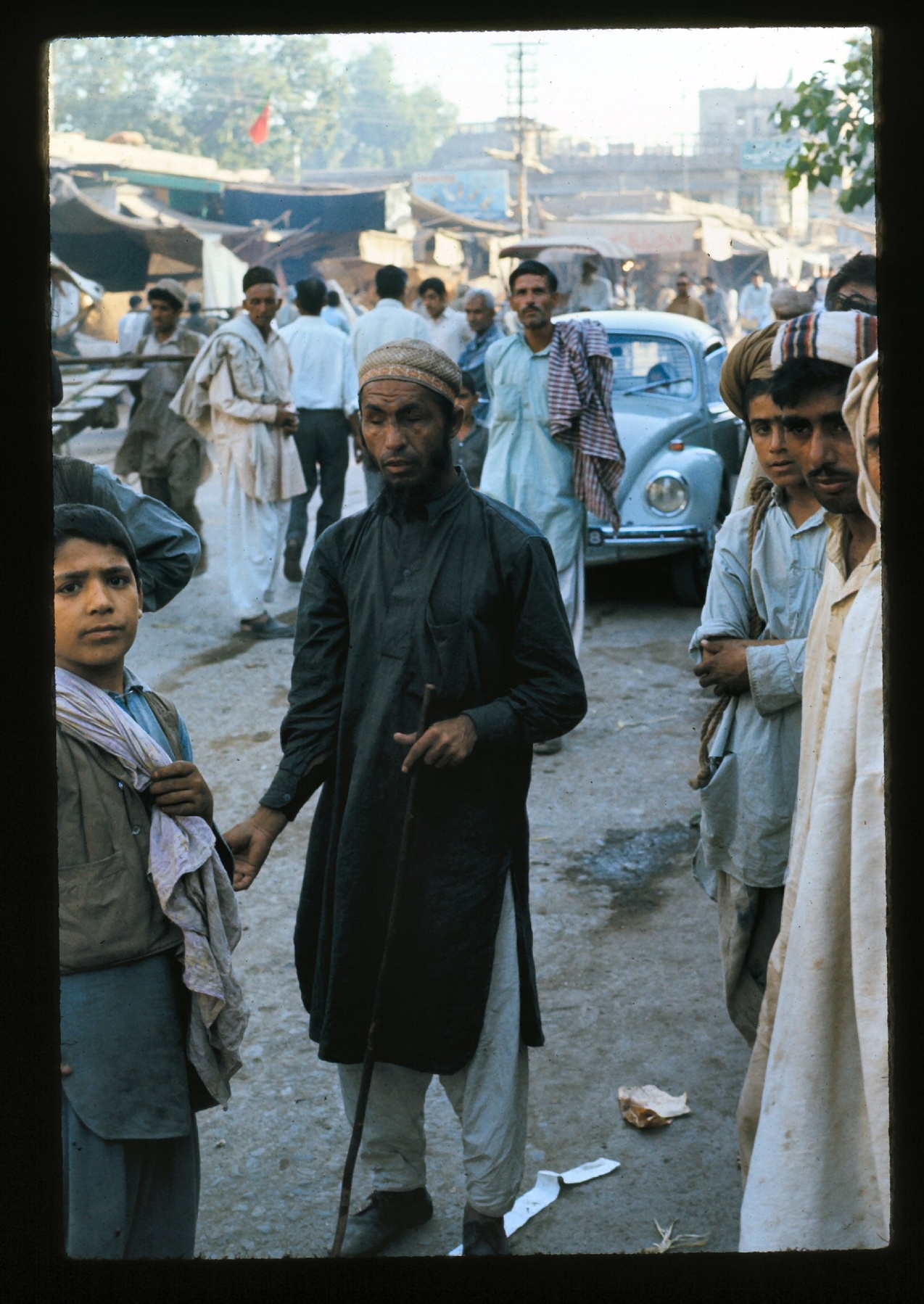

We got to Delhi at night. The other side of the world. Honking, crowded streets, crowded sidewalks, livestock, smog, and oppressive heat. The smells of exhaust, livestock, feces, charcoal, spices, and struggle, all mixed. As far from suburban California as I’ve ever been.

Outside a monument in New Delhi

New Delhi

New Delhi

New Delhi

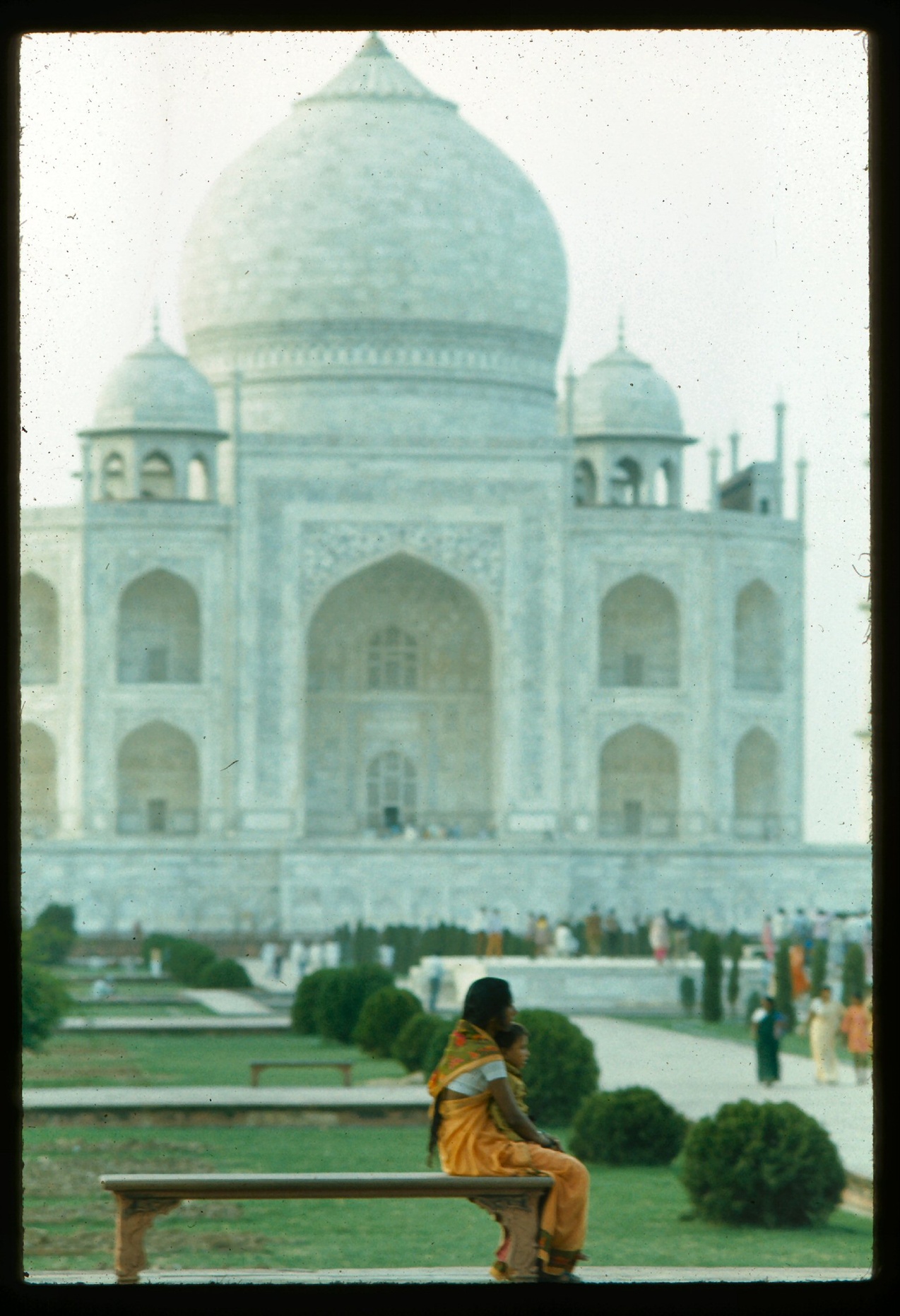

However, the Taj Mahal. They left us there for hours that seemed like minutes, It was so hot the tourists ran from shade to shade, literally. Beggars were everywhere. But the Taj Mahal is as majestic as El Capitan and Half Dome, huge, a proof of some kind of higher being, just as it stands there.

I’m told that the Taj Mahal is now blocked off. The last person I know who visited, maybe five years ago, said it was walled off, with admission severely limited. And outside the mobs of tourists and local people selling to tourists were horrible.

The Taj Mahal, below, is one of my better pictures. It’s impossible to understand from a picture how big it is.

It opens in the back to a dream landscape of ancient India, halfway around the world. The next picture below is the back side of the Taj Mahal. What you see here is heat. Like 110 degrees. Some of my group ran from shade to shade, like people do from shelter to shelter in a rainstorm.

The Taj Mahal in the distance, from the hotel. Hot, hot, hot. Well over 100 degrees.

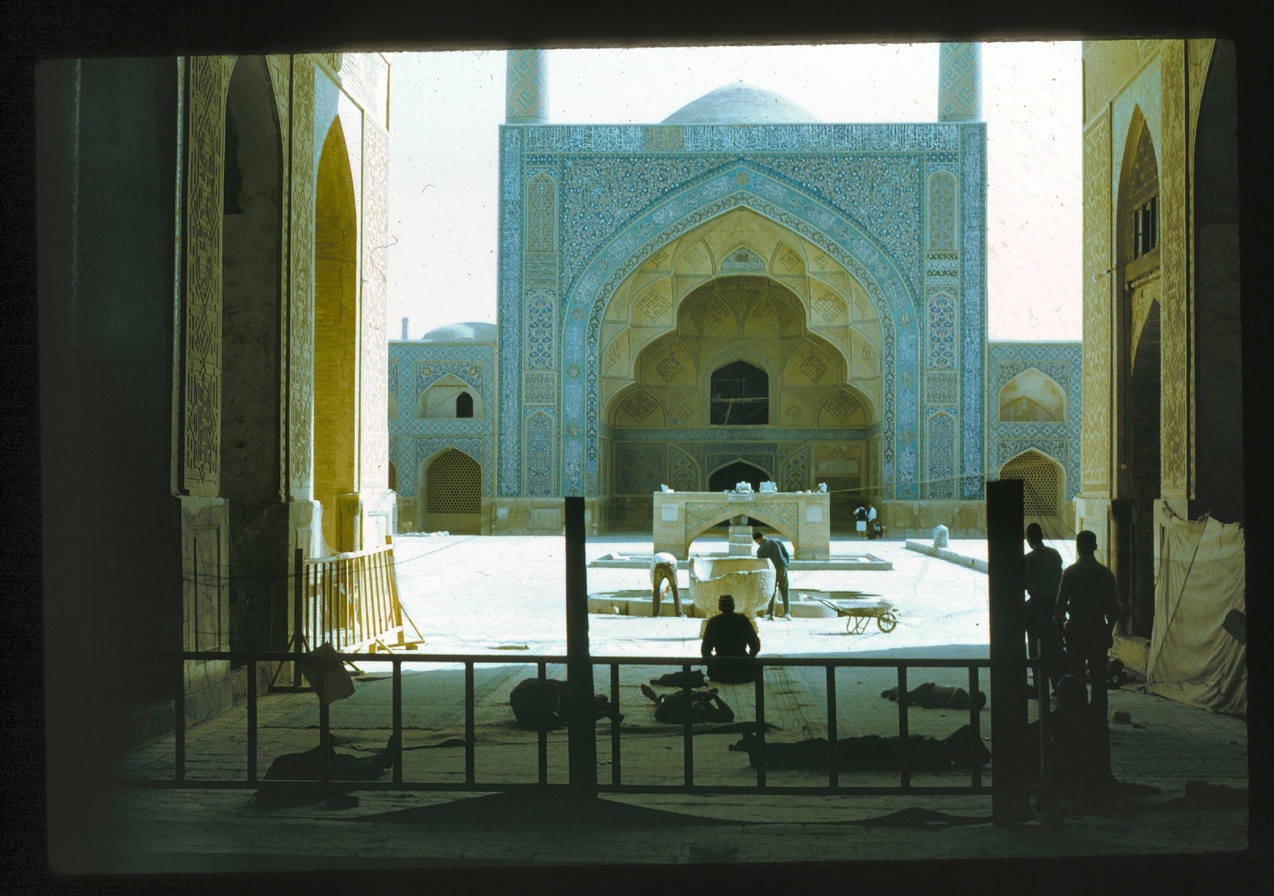

Iran

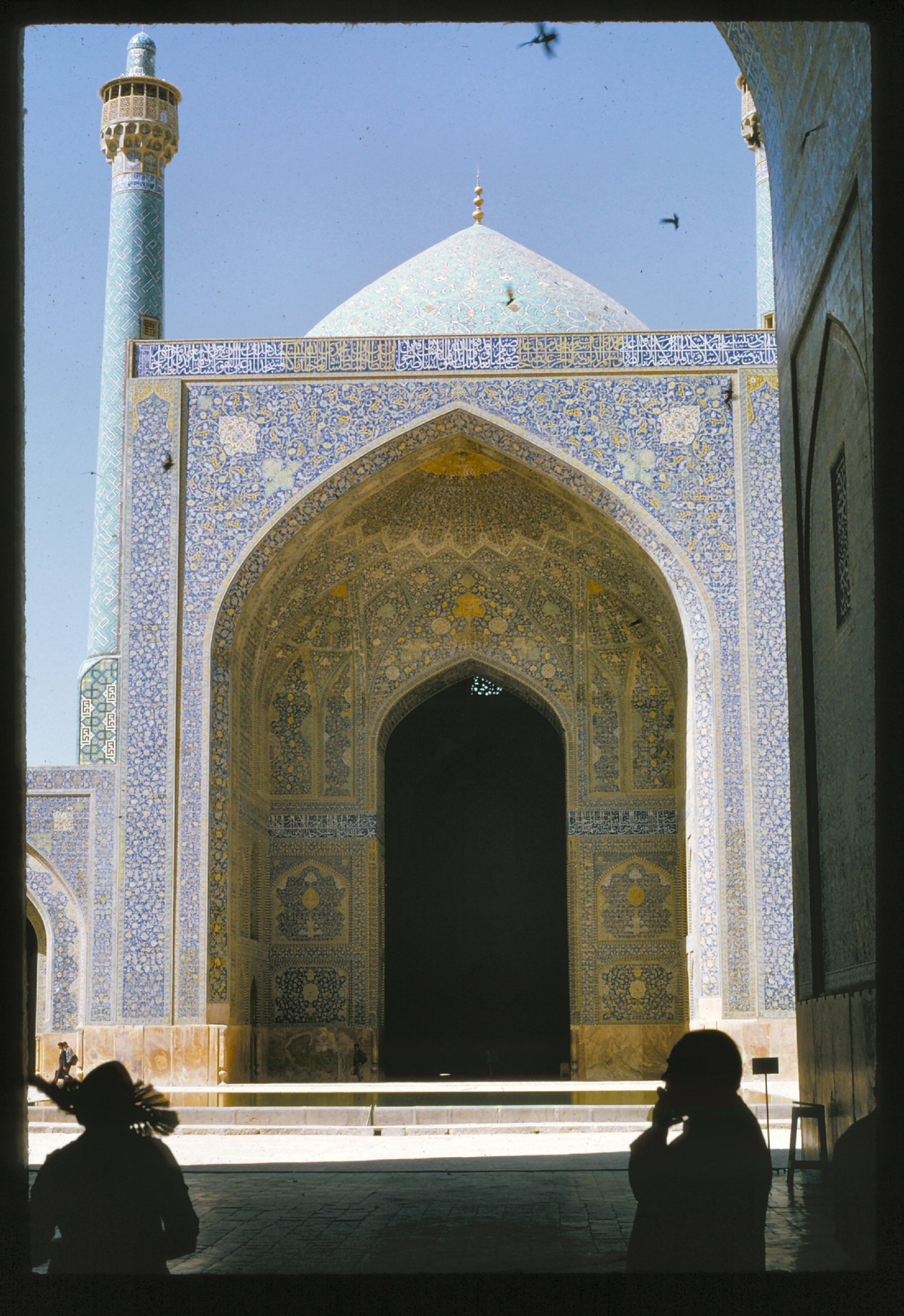

Iran was still controlled by the Shah. There were US fighter jets in the airport, and US business logos everywhere. Teheran was shopping centers surrounding mosques. Lots of Americans, a whole population of US oil expats. And lots of Americanization. This was six years before the Muslim government took over and kicked Americans out. We visited Teheran and Isfajan.

A view in Teheran:

Isfajan

Isfajan

Isfajan

Isfajan

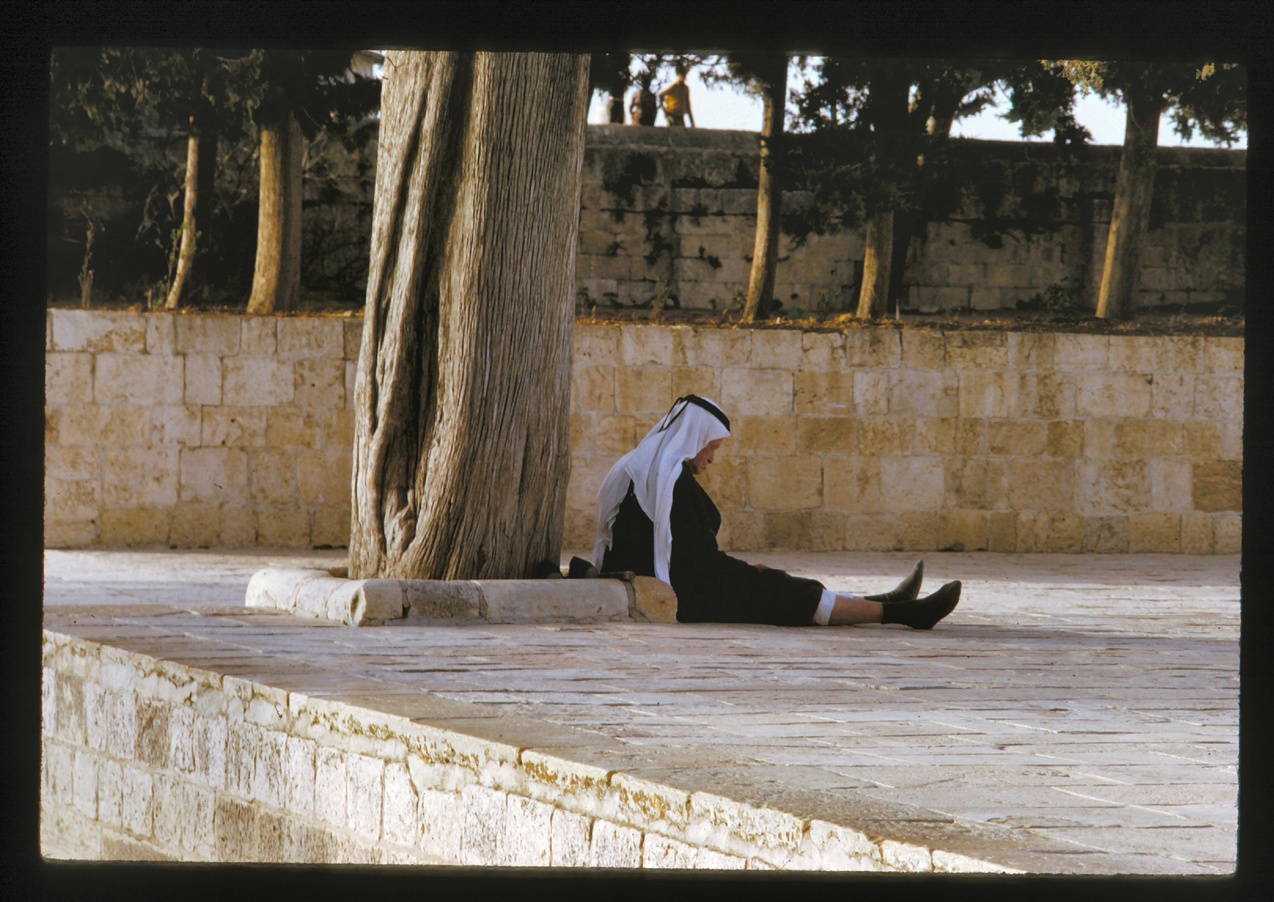

Jerusalem

In Jerusalem we ended up with a couple blocks of hours, and I wandered through ancient history, very narrow ancient streets, even the stations of the cross, the wailing wall, history alive. Tensions were high and security tight in May of 1973, just five months before the Yom Kippur War.

One immediate impression was about security. On arrival from Teheran, the security check to enter the country took two hours. Agents went through every suitcase. They checked ever toy, ever bottle, every box. Wrapped packages were unwrapped. We were all suspects.

One evening after dinner several of my tourists came to the beautiful hotel we stayed in, with a gorgeous view of the walls and the city, excited and full of their story. They’d taken a taxi down into the valley of the Dead Sea, which bordered on territory controlled by Palestinians. They walked out onto flats near the dead sea, apparently disoriented. They were captured by an armed car of Israeli soldiers and taken to a military installation, where they were treated like hostiles. Tension grew as the soldiers grew frustrated with their disoriented reactions. Only three of the five spoke English. Being Mexican, they were dark of complexion like Palestinians, but they weren’t. “Jews,” the soldiers shouted, asking whether they were Jewish tourists. “Jews,” they insisted, repeatedly, growing steadily angrier.

“Thank you, tomato,” answered the one in the group who was completely hopeless with English. There was a pause, and then laughter. The soldiers ended up driving them the hour’s drive back up out of the Dead Sea area to their hotel in Jerusalem.

The horse is a view from my hotel room in the Intercontinental Hotel, on a hill looking over the old city. The camel and jeep are from a parking lot in the hotel.

This is from the old city, along the route of the stations of the cross. By this time, two third of the trip gone, I was getting used to finding time to get away from the group and take long walks on my own.

Another view from the hotel.

Outside of Jerusalem, on the road to the Dead Sea.

Istanbul

Istanbul, as we neared the end of the trip, was the first place of all of them where I had actually been before, and, therefore, I wasn’t forced to fake it.

And that made it even easier for me to escape more on my own, take more long walks, and enjoy the travel more. I was a journalist, I’d taken a couple of courses on photo journalism, I had a brand new beautiful SLR camera, so on my walks I’d look for photos. And in the mornings, and evenings.

Istanbul

Why do I find the water, and ships on the water, so interesting? In Istanbul we had a hotel outside of the main city, along the Bosporus, with a view of the ships going by.

I took lots of pictures of the view from my room.

Istanbul

Istanbul

A small harbor outside of Istanbul.

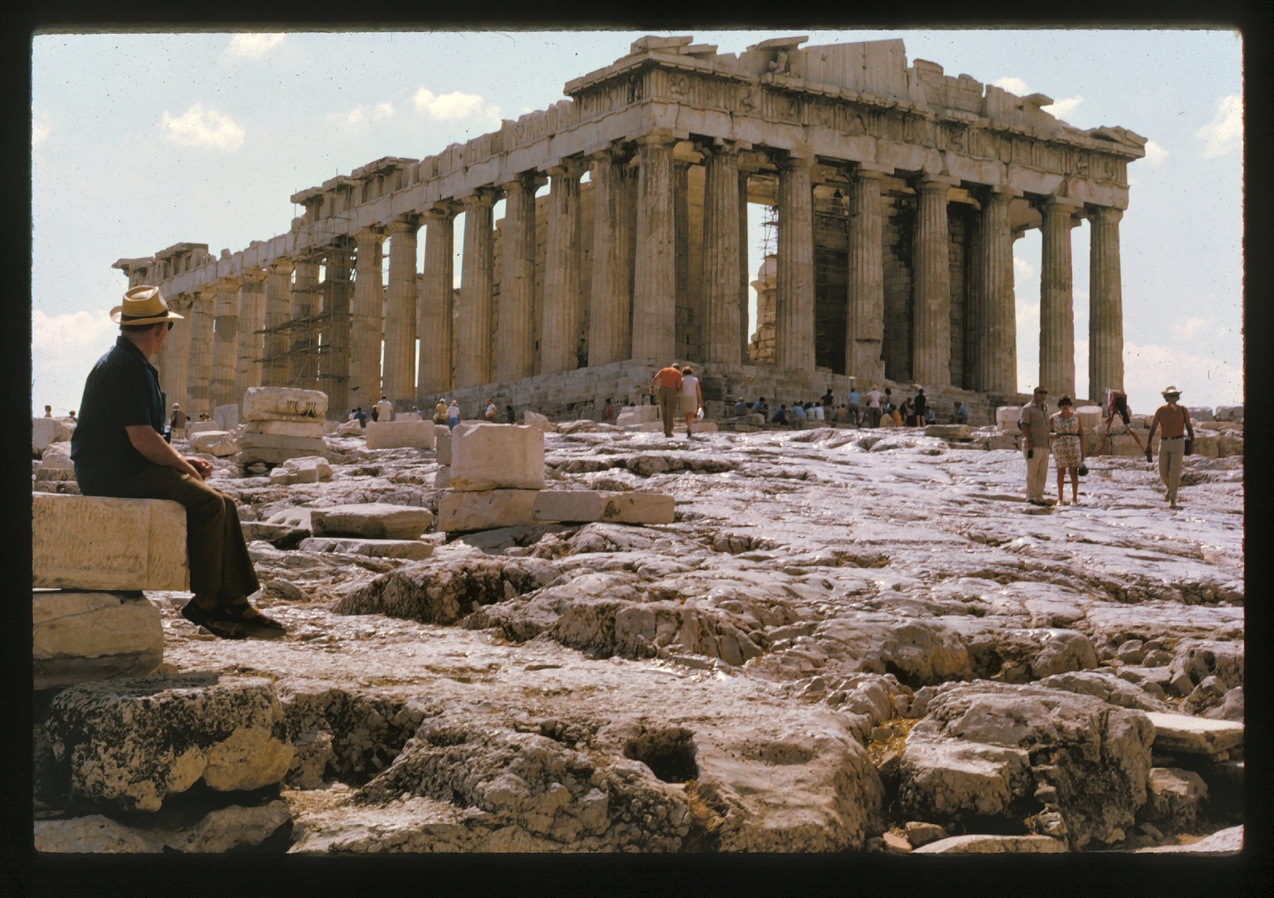

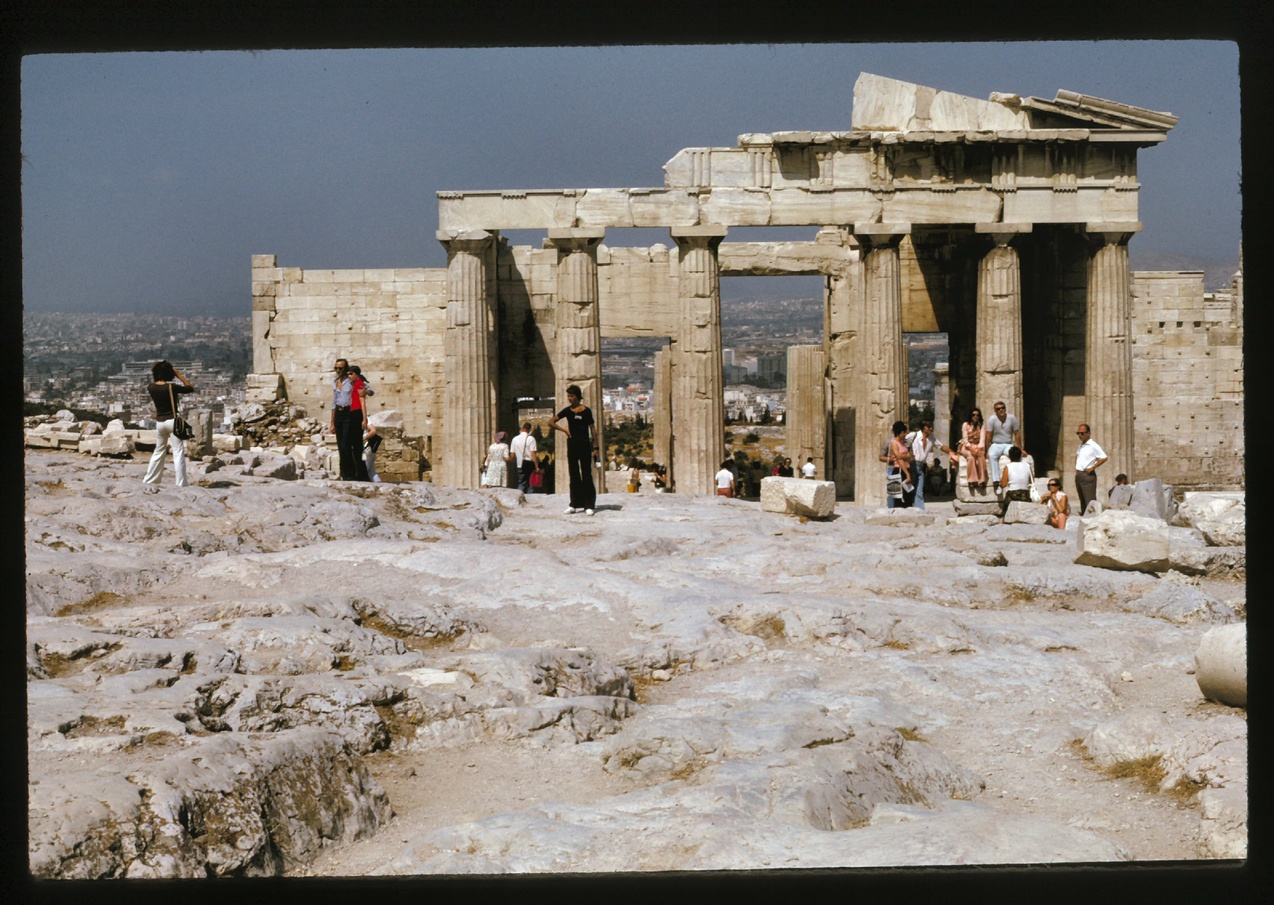

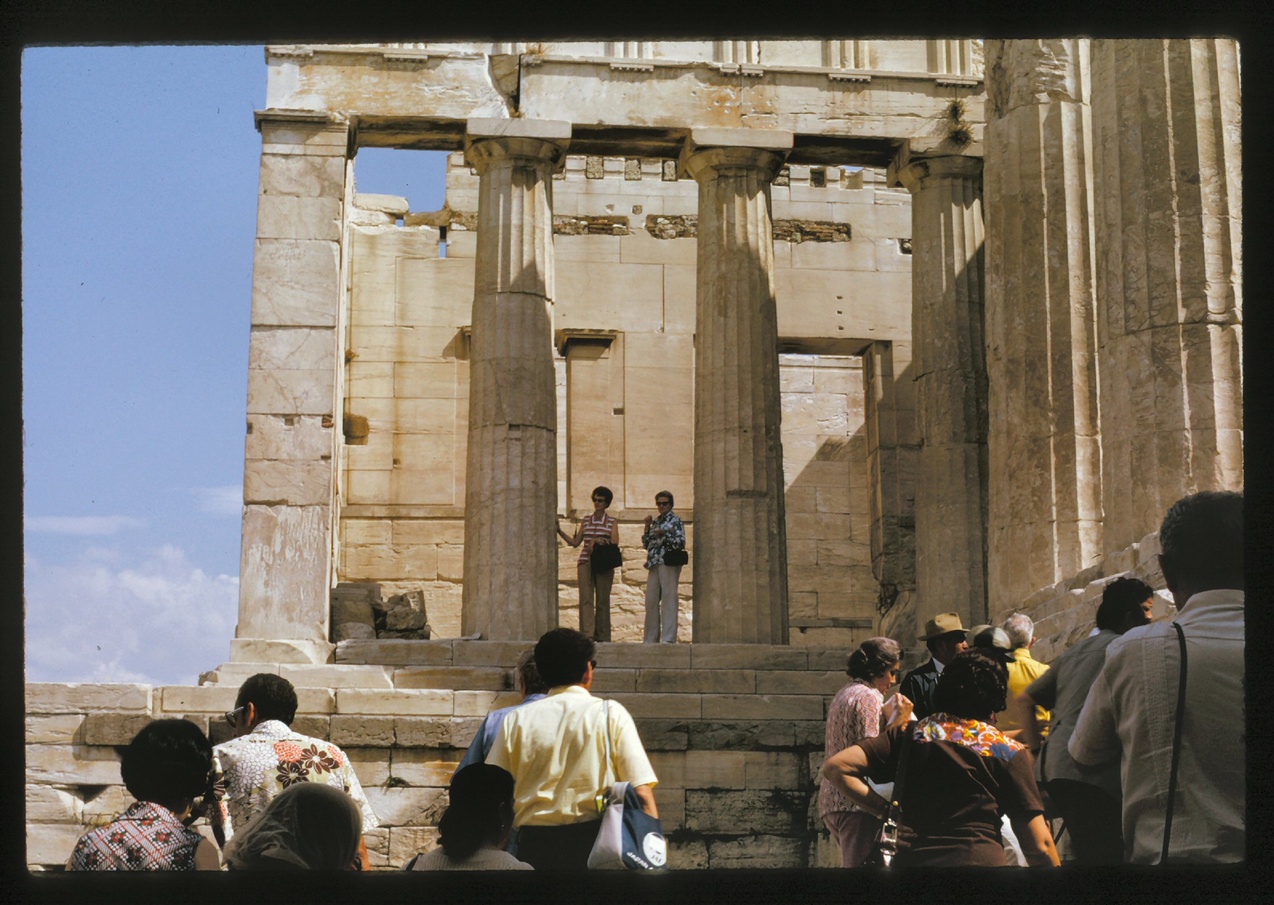

Athens.

I was so young, at 25. So much in love with my wife and missing her and my baby, Laura. Athens started to feel like the last stretch, finishing the trip. A gorgeous place, so again, I got off on my own for pictures.

By the way, the Parthenon was still accessible. It’s now completely blocked off to normal tourists. But in 1973 we could walk around at will.

Athens

Athens

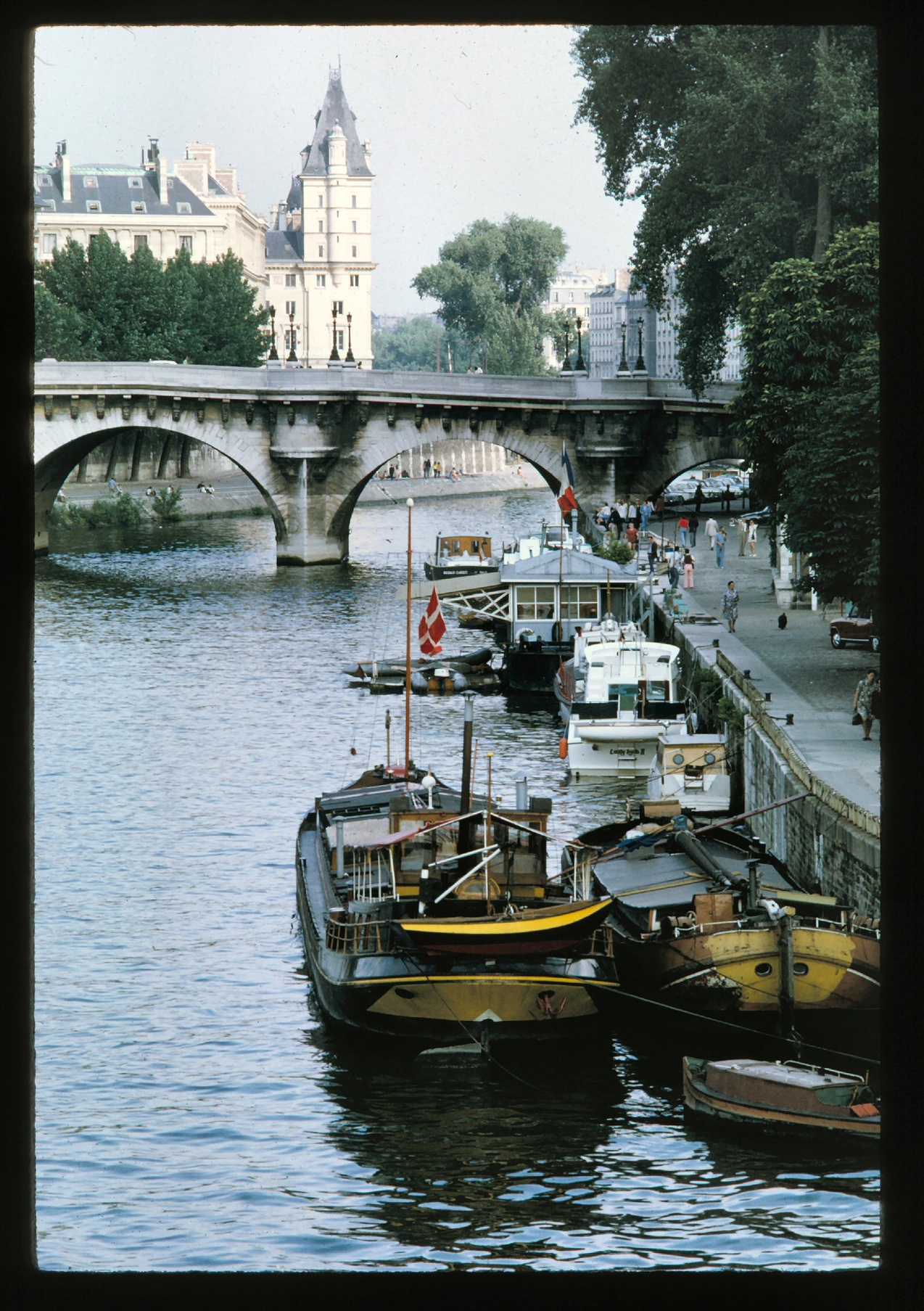

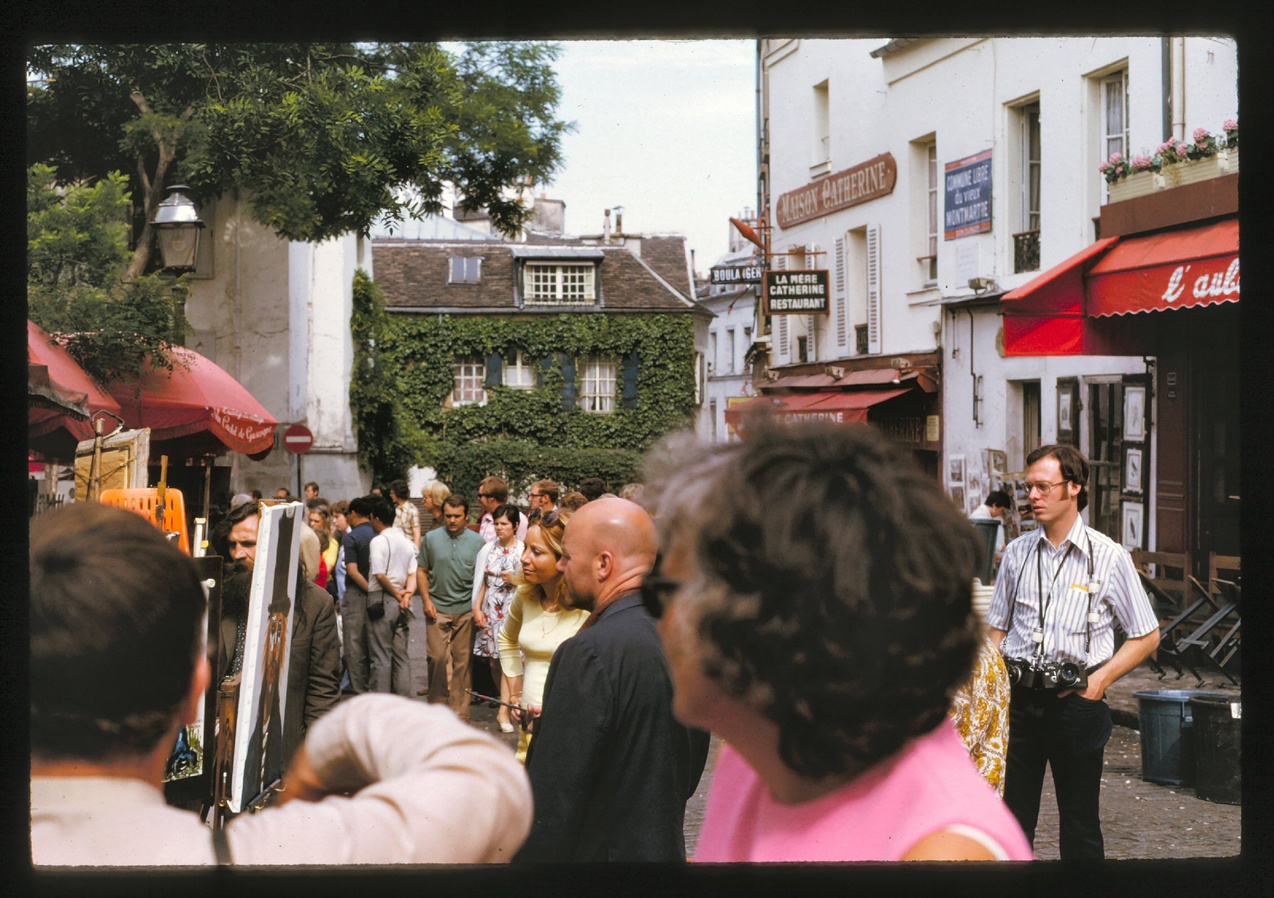

Paris

And then, finally, Paris. My third visit to Paris. And from there, back home to Mexico City.

And then, a long flight home. As I look back, 40-some years later, I’m sheepish admitting that during my first trip around the world, I missed Vange and home. But that was the 1970s, we were young, with young kids, and Mexico City and all; life was really good.

1973: Allende in the Hotel Garden

April of 1973. It was two or so in the morning. Pleasantly warm. I walked the paths that crisscrossed the interior gardens of the El Camino Hotel in Guadalajara, where I was staying. I couldn’t sleep, for a combination of stress and excitement. The El Camino was at that time the best hotel in Guadalajara, different from most, mostly horizontal. Connected wings of two or three stories of rooms looked over a series of interior gardens. I was there as a foreign correspondent, from the Mexico City office of United Press International, covering the state visit of Chilean President Salvador Allende to Mexico.

I came upon a small group in the lit garden, seemingly chatting, despite the hour. A man sat on a bench and 10 or so others sat on the ground, surrounding him. With a wave, the central figure invited me to join the group. The others turned towards me as I approached the group. And as I did, I realized that the man on the bench was Salvador Allende himself. Allende without advisors or security.

He asked me about me. I told him the truth: American, journalist. Looking even younger than my 25 years, and speaking fluent Spanish. He paused for a thoughtful second, then said (in Spanish, of course) something like “We are just talking. This is a group from the University of Guadalajara. And you are welcome to join, but as a young person, not as a journalist.”

So I sat down in the garden, and shut up, and listened.

And what was striking, what makes this remarkable even decades later, was how genuinely this great man shared himself with that group; and what he had to share. He was legitimately, sincerely, out to change the world. But, unlike so many others, not by any means. He was going to do it the right way. Using true democratic process.

For example, at one point he said Fidel Castro, his political ally, told him “to keep power, you have to kill like 500 guys.” (“Para mantener el poder, hay que matar unos 500 tipos.”) But no, he said, then he would just be another dictator, like all the others. When in fact (and this was fact) he had won his presidency in a true democratic election. He was there because the people voted him there, and — he was so inspiring — the time had come for real change, actual power to the people, because the people wanted it. Not just because somebody who had seized power wanted it.

Earlier that day, I’d attended and reported on a speech he’d made at the university. I was spellbound. His Chilean accent made his Spanish sound like poetry to me. And, much more important, his words, and his style, were deeply moving. He took on a hushed voice, almost quiet, when he talked about how his movement grew in the silence of the mines. Miners giving their lives, day by day, to enrich the mine owners (most big American corporations; he didn’t have to say it). And people wanting change. I had chills on the hairs of the back of my neck. And then he would up the volume, slowly, as he talked about the movement (the Chilean Socialist Party) grew slowly but steadily, a movement of people. And, as it grew, demanding change and power to the people, its opposition grew. His voice rose to a crescendo as he accused the United States, big business, and the CIA of doing everything they could to overthrow him, his party, and the Chilean constitution.

He treasured the Chilean constitution like patriotic Americans treasure the US constitution. It was a higher power than the political parties, international intrigue, his own party, or his opposition. And it was, in fact, in 1973, a working democracy that was 63 years old, had survived dozens of elections, and frequent changes of leadership and parties in power and parties in opposition. It was at the time the third oldest democracy in the Western Hemisphere, behind the United States and Canada.

That earlier Allende was Allende on stage, facing cameras, news media, a whole flock of professional politicians Chilean and Mexicans, plus a big auditorium full of students. That was also Allende in history, facing his place in history and his struggle to stay in power and protect his constitution from the business-driven power of the United States. That was the man I was reporting on during a state visit of Mexico.

What I discovered, in the garden in the small group, from two to four am, was that the real Allende was the same man. He wasn’t facades and personas. I believe I could tell. He was a brilliant man, and his power grew in the roots of his vision, his ideals, and his integrity. I dealt with politicians for almost a decade, as a journalist, out of Mexico City. I sat across the table from Mexican presidents several times. I interviewed Fidel Castro, Henry Kissinger, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan, among others. Castro had as much charisma, Kissinger had as much intelligence; but Allende was an idealist. He lived it and succeeded in building on integrity and ideals. And that’s what I saw, believed, and still believe.

Allende was a brilliant man, a true leader, an idealist, and a spellbinding speaker. He’d worked tirelessly for decades to oppose the US hegemony in Chile and Latin America, and the power of the wealthy upper crust and industrial monopolies. and Chile’s 1971 presidential election made him the first democratically-elected socialist head of state in history. And Chile was at that time the oldest constitutional democracy in Latin America. One thing was Russian and Chinese control of Eastern European and Asian satellite nations; and Cuba too. Having another Latin American nation “go communist” was an insult to the US, the Nixon administration, the Monroe Doctrine, and our national identity of good vs. evil. And soon after winning, Allende, true to his ideals, and supported by a like-thinking legislature, nationalized the mining industry, which meant confiscating the immense Chilean assets of big American mining conglomerates. The USSR sent money and resources, and Cuba sent hundreds of advisors. The US sent the CIA, its dominance of the continent, big business, and its wealth and power to get Allenda out. It was like 1914 with all the powers lined up for or against, and Allende and Chile the focus.

And, in the end, Allende was a tragic figure. My brush with him was in April of 1973. On Sept. 11, 1973, he was killed in the presidential palace by Chilean military troops under the command of Gen. Augustin Pinochet. Allende and the Chilean constitution were — exactly as he feared, exactly what he worked against — overthrown by the military with huge support of the CIA and the US establishment. He didn’t take Castro’s advice. He didn’t kill “500 guys.” He didn’t resort to dictatorial tactics. He didn’t change the world the right way, true to his ideals. What he did do was die trying.

1973: Headlines: Naked, Vicious, Brutal, and So Forth.

I was 26 years old. Married, already a father, but still, so young, and so full of illusions. I still thought – although I was starting to wonder – journalism could be about changing the world for the better. And not at all ready to accept the truth as Matt Kenny presented it to me that night, beer in hand, in a bar in Mexico City.

“Tim,” Matt said, “you have to learn about 50 words that will almost guarantee you play in the papers.” He swallowed. He looked at me and frowned. “But first I have to warn you,” he said, shaking his head, “you’re probably not going to like it.”

He swallowed again, then started listing the words:

“naked, violent, brutal, cruel, vicious, rape, clash, showdown, face-off, fists, bare, nude, stripped, fight … “

I can’t remember them all. Using these words, and combinations of them, Matt told me, would guarantee much better readership. Headlines with these words beat all other news stories.

This was in 1974. Matt Kenny, 50-something, gray hair, glasses, and quick to smile, was day editor for United Press International in Mexico City. I was night editor. Matt had been with UPI longer than I’d been alive. We were at that bar together that night because I Matt was a nice guy, a teacher at heart, and I was annoyed at him. So he took me out for a beer, to explain. To teach. And what he taught me 44 years ago is still true today. It’s true about headlines, readership, traffic, and people. Matt’s 50 words still work.

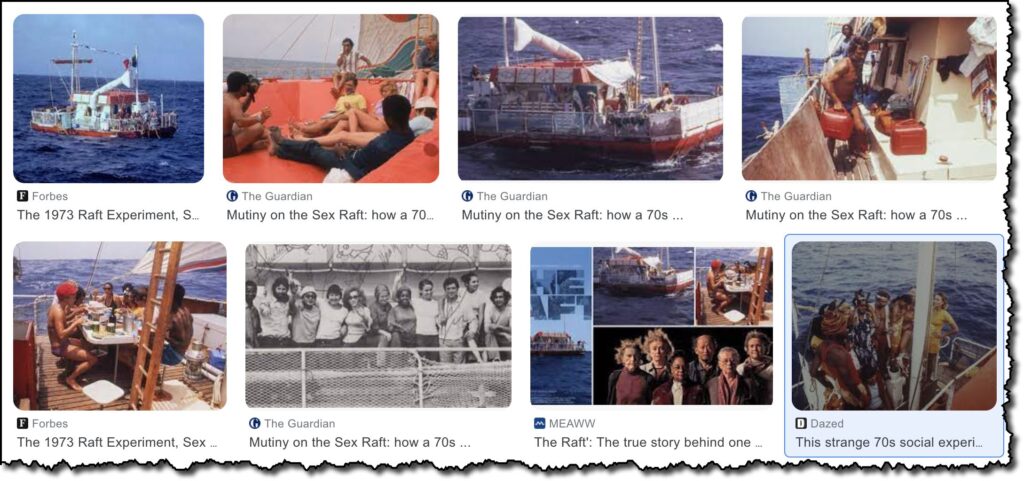

I was annoyed at Matt because a few days before he had rewritten my lead about the Kon-Tiki-like raft Acali arriving on Mexico’s Caribbean coast. I covered the story live, from Cozumel, and Matt handled it on the desk. It was a scientific expedition, a social science experiment, or so said the adventurous organizer. I wrote a lead focusing on the science, the experiment. Matt rewrote my lead to emphasize “suntanned bikini-clad” women and the co-ed journey across the Atlantic Ocean on a raft. He took the science out of it, and replaced it with the sex. Later, it became known as “The Sex Raft”; so Matt had a point.

United Press International, alias UPI, was a wire service with generations of history as the “other wire service,” the competition to Associated Press, AP, which still lives today. Mexico City was an outpost. We filed stories from Mexico City to the New York editors. The system gave the editors in New York our first sentence only, as they scanned new stories coming in. From that one line they decided whether or not they wanted to see the first paragraph.

That’s me in UPI office in Mexico City.

Matt was right, of course; I didn’t like it. And he was right about headlines. Matt Kenny was not unhappy or bitter or cynical or even hard-boiled. He was a pro. He did his job well. Matt’s 50 words don’t tell us anything about him — I liked him a lot, was proud to work with him — but they tell us a lot about us. I’ve seen it over and over in the years since. I see it in the coverage of politics, news, and life in general, not just in news media, but throughout social media. And in email subject lines too. That’s who we are. It’s not the media; it’s us. Now, about violence and the primary elections … do you think this is related?

1974: I Sold Out

Back in the late sixties, when I was a hippie and hippies were everywhere, there was this thing called “selling out.” The whole hippie culture opposed the “military-industrial establishment.” We were supposed to “turn on and tune out.” Employers were “the man” and getting a job was “selling out.” Particularly, getting a job in the establishment, as in for a corporation, or the government, or a successful corporate law firm … that was selling out. And it was a bad thing.

I lived that ethic. Other stories here talk about me leaving home and going to the Haight Ashbury to be a hippie. I protested the war in Vietnam, protested pollution, protested Richard Nixon and LBJ. Even after I met Vange and married, I was going to be a poet, or maybe a literature professor. and never “sell out.” I veered to Journalism (another story here: “1971: Becoming a Foreign Correspondent” ) and that was not selling out at all. I was going to tell the truth. Fight the military industrial establishment with the truth. I believed that down to my bones.

Sure, I have to admit, the Journalism I got into was steeped in journalistic ethics. I lapped that up in my studies for a master’s degree. I truly believed, also down to my bones, in the value of telling the truth, reporting accurately, separating reporting from opinion. So too, back in the 1970s, all my professional colleagues. We believed in the mission. Journalism, in fact, easily overrode the idea of representing some sort of hippie values. Journalism was ethical to the core.

In October of 1974 I was offered a combination of a fulltime job with Business International (which no longer exists) and an exclusive stringer/freelance relationship with McGraw-Hill World News, which published Business Week and several dozen other business magazines. That was clearly selling out. I felt it, I regretted it, but I also did it. I rode journalism into business writing and out of general news reporting. Which was, by any and all of my closely-held hippie values, selling out. I was going to be writing for Business Week and the like, definitely the military-industrial establishment.

I’d been mainstream journalist from June of 1971 through October of 1974. I covered hurricanes, kidnappings, volcanic eruptions, politics, leftist guerrillas, tourism, whatever the world wanted to know about from Mexico. But that changed.

Why? Family plus some growing up. Going from UPI to business writing doubled my monthly earnings. And we needed the money. By 1974 we had Laura and Sabrina. I sold out the same month Sabrina turned one year old. We had a fifth floor walkup apartment and an old VW, the same one I bought in Munich in 1968. I wanted the luxury of having a car that would start when I turned the key, more time on weekends with my family, a better apartment, and money to spend on the family. Selling out was part of it and I didn’t deny it (actually there was no oppportunity to not deny it except to myself; nobody else cared. Nobody else in that world even understood the issue.

So I sold out. And, as it turned out, took a step towards who I was supposed to be. Business writing led to wanting to actually do business, not just write about it. And that led to my Stanford MBA and from there to Palo Alto Software.

I have always carried a bit of baggage about it, selling out, as kind of a rueful pool of memory of how idealistic I once was. I don’t regret it for even a second. Building Palo Alto Software was huge and way more ethical than hanging around without having sold out, writing poetry nobody was going to read; or, for that matter, staying in Journalism, filling the spaced between the ads. I did business plan software that empowered millions to take steps towards building and owning their own businesses. Literally, millions. We sold it at fair prices. Palo Alto Software has employed hundreds of people through the years, given some great jobs and benefits to me and my people, and helped us all. Palo Alto Software employees have, in the meantime, had lives, bought houses, helped the local economy. I thank God I sold out.

1977: Me in Cuba with Fidel

Castro, in person, was amazing. I loved the guy. I should remind you that my Spanish was fluent by 1977, when this happened. It was six years since we moved to Mexico City and my life there was in Spanish, from the radio talk in the car to all the dealings in the office. I was even writing finished copy for the UPI news service, in Spanish, for some sporting events that required instant posting.

Castro held court for more than two hours with more than a hundred executives of multinational corporations, about half of them American. He gave a short speech to start, but most of this was free-wheeling answers to the executives’ questions. He’d raise his voice at times in anger, and I’d seeth with him over the injustices inflicted on him by the American power. He told us that for years he never slept in the same place two nights in a row, because the CIA was so determined to assassinate him. And when Castro spoke, I believed. Then just a few minutes later, he’d lower his voice, in complete sincerity and conviction, as he talked about his goals, his dreams, what he wanted to do for his people. And over and over he’d answer with wisecrack and instant wit to rival the best of the best standup comedians. Over and over he’d raise the hairs in the back of my neck as he fell into his quiet and almost poetic best visions. He was a master. I would have followed him anywhere.

I took this amateur-looking picture and it’s the only one I have. Castro was charismatic and cordial with the executives who attended. Here he was signing autographs. I didn’t get a picture with him and me in it because I was mostly in the background, doing the work.

No, I didn’t get him alone, or in a small group. There were more than a hundred people in the room. But I sat near the front, on one side, taking notes, getting a privileged position because I was charged with reporting it.

I was also favorably disposed. I came to the occasion after my hippie-oriented youth, the summer in Haight Ashbury, the cumbaya group in the Trinity Alps, marching against the war in Vietnam and for civil rights. I’d had a lot of reinforcement from my colleages in journalism in Mexico City, Latin American correspondents, generally sympathetic to Cuba and distrustful of the U.S. My understanding of history had Castro as the freedom-fighter leader that kicked Bautista the U.S.-supported dictator out of Cuba in 1959; who turned to Russia for support and safety only after the U.S. had thoroughly rejected him. And my understanding of Cuba had it as an exceptionally poor country because of U.S. sanctions, but still one that treated its poor better than most other Latin American countries. At the foreign correspondents’ club in Mexico City, people said that Cuba was the worst place in Latin America for the rich, but the best place in Latin America to be poor. The poor in Cuba had better schools and medicine than the poor in any other Latin American country.

Going to Cuba for six weeks was a big deal for an American in 1977. It was the cold war. The US had severe restrictions on American travel to Cuba. It took exemptions and approvals from the American government, which were available because I was working at the time for Business International, so there was business interest. And Business International had some leverage into the government through CEO Orville Freeman, who had been a Nixon cabinet member. It also took getting a visa from the Cuban embassy in Mexico City.

It happened because sugar crops elsewhere failed in 1977 so Cuba’s sugar was suddenly and all at once way more valuable than it had ever been. That meant Cuba had an influx of hard currency. Unlike all its Castro history before 1977, Cuba could purchase goods from western nations, maybe even from the U.S. There was even talk of Western foreign investment. Business International, meanwhile, served more than 300 multinational corporations with newsletters, seminars, conferences, and consulting. So Business International set up a foreign investment conference in Havana. More than 100 multinational clients agreed to attend, pay a hefty fee, and send senior executives.

And that led to my being included. By that time I’d been with Business International three years and they liked me and my work. My Spanish was fluent after six years living in Mexico City. I was a damned good journalist. I had co-authored book-length studies on international business and the Mexican economy. They needed a book-length study on opportunities in Cuba, as part of the conference. So I got to go to Cuba in 1977. American, or not. And I got there bringing along, quietly, secretly, my sympathy for Fidel Castro.

The picture above is me in the office we worked in, with one of my Cuban teammates, holding the book-length study we did for the conference. If you look closely at the picture of Castro above, right above his hand, the corner of that study is sticking out from the arms of one of the officials.

And, sadly, that sympathy for Castro died during my weeks in Cuba. I came expecting to see a heroic people fighting against all odds for freedom, justice, and equality. I left with my illusions punctured, feeling confined and claustrophobic in a country with no freedom, people who spied on neighbors and turned them into dark secret police, who lived in fear.

What happened? What changed my mind? Several weeks of working on a book-length economic study of foreign investment opportunities in Cuba as part of a team. It was me and two other Business International employees, business journalists both of them, one Latin and another American with deep ties to Spain; plus three Cubans who were assigned to the team. One of the Cubans was the driver, the two others were economists supposed to help us do the study.

Working side-by-side with my Cuban colleagues popped all my illusions about Cuba. As time passed I realized, more each day, that each of the three of them was afraid of the other two. They never let down their guard. They took us to meetings with public officials, to historical places (most notably the Bay of Pigs, where Cuba defeated a JFK attempt to take Cuba back from Castro in 1962), even to ought-to-have-been fun places like the most popular beach and downtown Havana old section full of music and restaurants.

Restaurants were lively, generally full of music; but the food was dull. Everything available seemed a variation on rice, black beans, and fried bananas. Shredded pork or beef was prized as a special dish, even though the meat was stringy and tough. Fish, surprisingly, was rare.

The cars were overwhelmingly older American cars from the 1950s.

Our hosts, the Cuban organizers of the conference, seemed to make daiquiris instantly available to all of us at all times. Cubans circulated through every meeting and every event with full trays of daiquiris. After time it felt more intentional, sabotaging us by preying on our weakness, than hospitable.

The three Cubans were always wary and tense. They laced slogans and revolutionary patter throughout their conversations, with us and with each other. They competed constantly with each other on who could most use the word compañero (comrade). And so too on who most loved the revolution, Cuba, and Castro. There was never a slip in conversation that might have indicated some dissatisfaction with even the tiniest detail in their lives. They had no complaints, ever, about old cars, refrigerators, work schedules, food, anything.

And finally, there was the special claustrophobia of the opposite of free enterprise. By 1977, although I was still a business journalist, I was starting to dream about owning my own business someday. I was making more money with freelancing than the salary that Business International paid me as an employee. I was close to Raul Garcia Moreneau, Vange’s sister’s husband, who owned and operated his own travel agency. I spent a lot of time with Raul and Vange’s brother Horacio, who was a salesman for Gillete. Horacio and I often dreamt out loud about owning a business, and Raul, who did own one, encouraged us. During the weeks that I worked with the Cuban colleagues, I came to realize that the one who was a driver had no hope of ever going out on his own and owning several limos, or starting a travel agency. The ones who were economists had no hope of ever going on their own and taking on private clients. Their only hope for advancement depended on convincing their use of “compañero” and revolutionary clichés. Success and promotion was about loyalty, not work, or even competence.

I flew back to Mexico City on an evening flight on a Cuban commercial plane that was propeller driven and older than I was. The bureaucracy and red tape and inspections and such had been onerous on arrival, but seemed much worse to me as I was leaving. All I wanted from Cuba, at that point, was out of there. Getting back to Mexico was a huge relief.