1964. The year of the Beatles, Mario Savio and the Berkeley Free Speech. The year I also began protesting the Vietnam War, racial segregation, and environmental pollution. The year I took my first trip alone up into the High Sierra After the Sierra Club trip in 1963. The year I first grew my hair long, fought with my parents, and got myself switched from public to Catholic high school for straightening out.

Two months either side of my 16th birthday, January, 1964: John F. Kennedy was assassinated two months earlier. The Beatles arrived in the US one month after.

Resonance with the Rest of Humanity

For me 1964 started with my driver’s license in January. The driver’s license was the pinnacle achievement of reaching 16 years old. I took the test on my birthday, having badgered my poor mom into driving me into the Palo Alto DMV that same day, as my favorite birthday present. Coming of age for me and most of my peers was not drinking age, not voting age, but driving age. Independence. Behind the wheel. I didn’t have a car, but I had access to cars. And girls I hoped to date.

In my case this coming of age felt like resonance with the rest of humanity. The times were as fresh as bright green Northern California rolling hills dotted by dark green live oaks, after a spring rain, smelling of rich warm damp seeds and growth bursting at its seams, under an intense blue sky framed by clean greens. A world ready to burst open and flower. It felt like I was part of a huge wave, surfing history, an entire generation going to change the world, end war, defeat the military industrial complex, turn politics inside out, stop pollution.

It wasn’t just me. It was 1964 everywhere.

And because of my age then, this was all also inside out for me, with the world seeming to match, on the outside, what was happening for me, inside, inside my head, out of my eyes. This burst of the sixties coincided with my own growth spurt, voice changing, and the amazing excitement and passage of the driver’s license. It also coincided with the natural fascination, absolute obsession, with the magic of girls. Everything feminine, of course the curves and shapes anatomy and biology, but also voices, faces, literally, every tiny nuance of the amazing differences between them and me.

February 9, 1964. The Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan on Sunday night. Television was still black and white. Seventy-three million people watched, spellbound. They did five songs from their first album: She Loves You, I Want to Hold Your Hand, All My Loving, Till There was You, and I Saw Her Standing There.

The Beatles changed everything. Back then our music listening was limited mainly to what we got on the rock stations in radio. From then on, whenever a Beatles song came up on the radio, we all agreed to stay quiet and listen. “Stop. This is the Beatles.” Even Mom and Dad forgave us that. All the kids did the same. We were driving by then, so the Beatles became the most important moments in car travel. (Except for my brother Chip, who was 17 at the time. Chip remained loyal to Wagner and opera until he discovered the Beatles and the Beach Boys, a few years later, at Pomona College.)

The Beach Boys were also popular. And the Temptations, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Bob Dylan, even (still) Elvis Presley. But for the Beatles, and only for the Beatles, talking stopped. It was a Beatles song.

Beatles were a cultural event too. Their arrival in New York on February 7 was on all the major news shows, with teenage girls screaming their heads off, and huge crowds gathering.

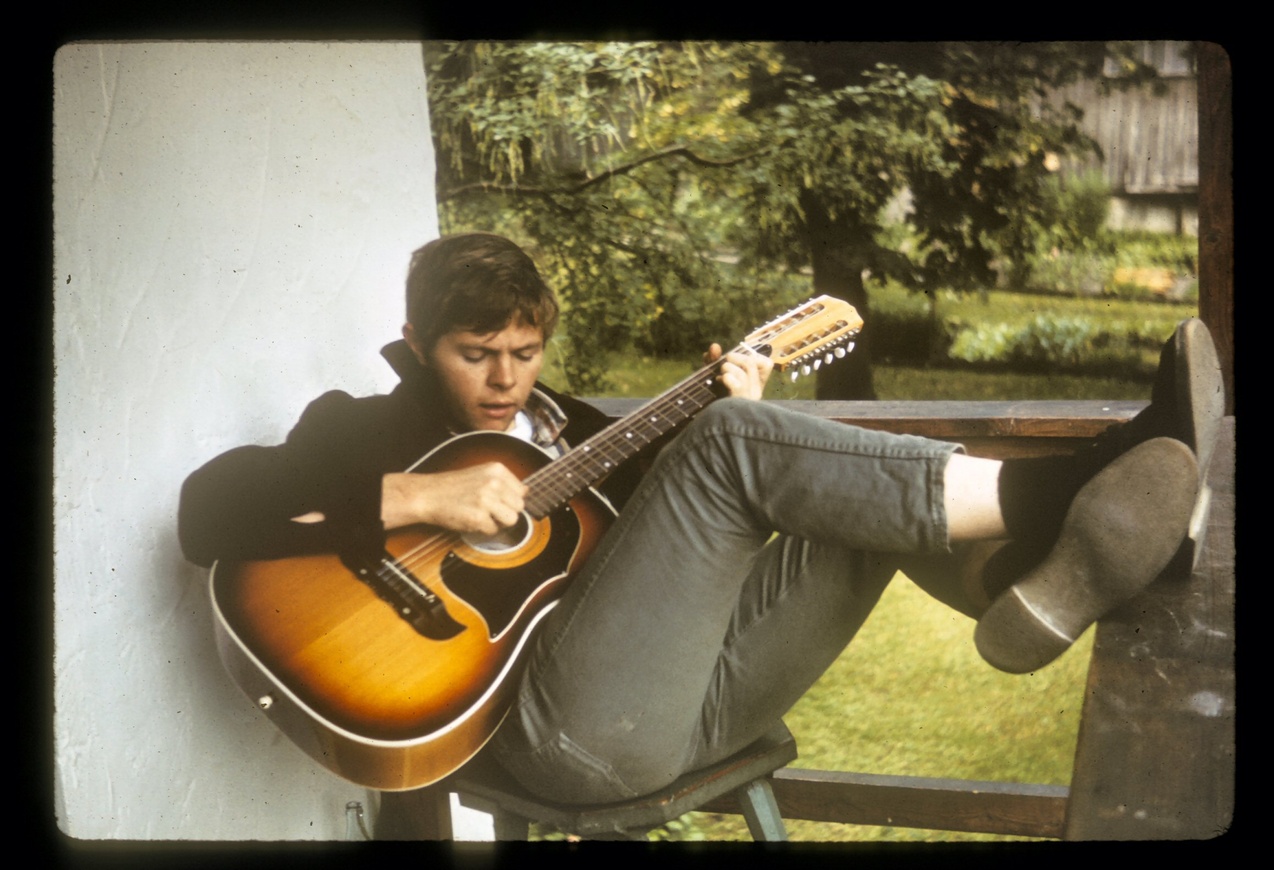

Their look, which would seem so innocent after even just a few years, sparked a new battlefield between parents and sons. The Beatles innocent bobs of hair were taken as long hair, unkempt, disrespectful, revolutionary. They tracked to the Free Speech movement, the student rebellion, distrust of authorities, and, in just a short time, the whole concept of hippies. Immediately me and every friend I had, plus most of the other guys our age, wanted to grow our hair like Beatles. The long hair became the flag and banner of hippies, the new world, the calls for change. Kids left home over it. Parents kicked them out. The battle had been called.

And from there, with the Beatles, hair became the symbol of protest, the divider between generations. Kids became hippies. “Don’t trust anyone over 30” was a common cry in the generational war. So-called hippies, mostly kids with long hair and dressed in the hippy-influenced style of the time, were everywhere. In the Bay Area, by 1964, hippy style was the default for all teenagers, not the exception.

By 1964, the Vietnam War was reaching the nightly news and gaining public attention. We saw helicopters and troops, thumbs up signs and such, and occasional shots of troops firing and under fire. Technically they were still just US advisors, but they sure looked like troops on the news. A few people (and me and most of my friends) opposed the war this early, because it supported a corrupt regime and foreign intervention. But it was still public policy. The domino theory reigned supreme in Washington. And at this point, most of the public still believed what the government said about the war, the need for the war, and fighting communism. Dad was a staunch supporter, while Mom and her kitchen pundits began to doubt.

July 31, 1964. The Gulf of Tonkin incident. A minor navel skirmish in the waters outside Vietnam. It played heavily on our nightly news. It was followed on August 7 by the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which essentially authorized Johnson to conduct full-scale war in Vietnam. And years later, it turned out that the incident was largely manipulated by the Johnson administration to create a justification for escalating the war.

1964 also hailed the free speech movement in Berkeley. It was the first of many organized student protests in the 60s. Its most visible leader, Mario Savio, was a national hero for youth, and goat for adults. It exploded over university rules that limited political campaigning and activism on campus to clubs representing either Democrat or Republican parties. Activists were protesting the Vietnam War, Racism, pollution, and so forth.

The clashes started in October 1964 and continued off and on for most of 1965 and even into the following years. Chip was a law student at Berkeley and got caught in the tear gas at least once.

In November, the 1964 presidential election. That election divided my parents and a lot of the country, much more than Kennedy vs. Nixon. Johnson vs. Goldwater was a clear choice between Johnson’s moderate “Great Society” and Goldwater’s (in my mind) extremism. Goldwater was a hawk. The Johnson campaign tied him to nuclear war and mushroom clouds. Nobody I knew wanted Goldwater except Dad.

Mom and Dad squared off with Mom firmly for Johnson and Dad almost as firmly for Goldwater. Discussions around debates and TV commercials generated frequent arguments, many of them followed by long periods of angry silence. Goldwater was so true to his conservative ideals that he made Johnson look good. Johnson’s 60% victory was the largest margin ever.

And yet, as it turned out, Johnson too was a hard-liner hawk. He turned aggressively to win the war in Vietnam, without much regard for protests, or truth. His administration created a trumped-up incident in the Gulf of Tonkin to gain public acceptance of sending more troops. They lied about the progress of the war, the death count, and the corrupt politics of South Vietnam. He became a symbol of the military industrial establishment that — we were sure — was running the nation.

Growing Up. My 1964

February 10, 1964. Monday. The day after the Beatles’ first US appearance on the Ed Sullivan show. In the middle of a California February afternoon, sunny, I sat comfortably on a typical yellow school bus bench seat, spread out on one seat, glowing inside for the casual attention of three girls within earshot.

The bus wound through the big sprawling houses of Los Altos Hills at the top, up Magdalena and back around to Mora Drive. Where I lived was the last stop before school, an advantage in the mornings, but a long ride in the afternoons. Every day it took an hour to go all the way around the hills and get home.

The ride was okay because those three girls, one a senior, one a junior, and one a sophomore like me, were temporarily accessible for idle conversation like normal humans. Not, as they were for most of the day, goddesses. I was an equal. We talked about the Beatles, their sensational debut the night before.

It was probably on that bus, in 1964, that girls turned gradually into humans, for me. I was a sophomore in high school. But the license meant nothing without a car, and even a car would have meant little without a girl to invite on a date. That too happened that year, for me; but later in the year.

By then it had been two or three years since I’d woken up to their existence as something higher, brighter, much more beautiful than a normal human being. I saw their new curves, and noticed their manner, so delightfully different than me and my friends, the boys. I was in Los Altos public schools, so we grew up together, in elementary and middle school. But girls, just as girls, were magic. Looking back, our generation didn’t have porn of any kind. Yech. Our boy imaginations went wild with what we had, a touch of underwear ads, gorgeous movie stars, and yes, the girls around us. Goddess is an apt word. As went through puberty together they became luminous. And inaccessible. And magic.

That daily bus ride, that year, was a breakthrough. It took me until the following fall, in a different high school, to actually invite a girl on a date, the homecoming dance, holding her magical hand and dancing with her, and the smell of her all dolled up. But on the bus ride, talking about the Beatles, they returned to humanity. We could talk. There were still people living in those bodies, some of them even the same people they’d been in elementary school, when they were just girls.

I might have been a nerd, if we’d had that word, because I was good at school. But I was also good at sports and girls liked me. I was too chubby, but I was one of the better athletes on the playground, a captain of the middle school football team, a big hitter on the baseball team, so I wasn’t subject to the teasing I might have been. I was fine with the girls in elementary school, but too shy in high school.

Girls, especially these smart, pretty girls, were still goddesses, not to be approached … except for the irony that on the bus, removed perhaps from the normal social structure, they were just plain friendly, like people.

In 1964 that Oldsmobile convertible, the one that had made Mom cry, came of age along with me. By that time Mom had forgiven it. It had taken us for a once-in-a-lifetime father-and-sons fishing trip to Castle Crags State Park. It took us to Stanford Football games. What a car. Huge, for one thing. Literally 18 feet long and 6.7 feet wide. With a 315 Hp engine. And convertible.

We had also discovered that convertibles made no sense. Not even in California, the best weather possible. It was cold at less than about 72 degrees, and too hot and sunny at anything over 80 degrees. So, the red convertible lived with its white top up, slowly rotting. It was cold, windy and noisy. Dad kept me away from it for as long as he could. But there were those special odd times when I tooled around Los Altos in it. When I stomped on the accelerator — which had to be away from home, for obvious reasons — it could burn rubber for five or ten seconds, 50 or more yards. It was too much car for a young driver. I was bad with that car, and it urged me on when I was.

Around the same time, my PE friend Terry McKenna invited me to join his after-school group that they called — because Awalt High School demanded the formality of it — the Foreign Affairs Club.

Terry was a gangly, awkward guy, a year older than me, super smart and wicked funny. He and I loved to make wisecracks from the sidelines, potshots at the PE teacher and some of the more annoying classmates. Terry was fun. His club was about the same kind of issues that were in the air, in the environment around us; and that same Spring, in 1964, crystallized as the Mario Savio Free Speech Movement in Berkeley.

Hippies captured our imaginations. Styles, and thinking, gravitated towards the hippies. Berkeley, with the Free Speech Movement, and San Francisco, with a collection of new psychedelic rock groups, became a center of it.

Terry McKenna went on to become a folk hero for a subset of extreme intellectuals who connected higher math with higher consciousness, LSD, and the enlightenment concepts that had begun a couple decades earlier with Aldous Huxley’s Doors of Perception, mixed with measures of eastern philosophy and political rebellion.

Summer of 1964 I got Fred Klein, a classmate at Awalt, to join me in my first backpacking trip in the Sierra. Fred was vital because his mom let him take their car, a 1950 Buick, so we were able to get there. This first trip was where I discovered everything not to do with backpacking. If it weren’t for the glory of being in those mountains, it would have been a nightmare.

I equipped myself as best I could, with a heavy cloth sleeping back, a barely acceptable backpack, a heavy cloth sleeping bag, and incredible extra weight including a book on the flora and fauna and fishing equipment with multiple bait and lures. My pack weighed at least 60 pounds, probably more. We had bad cooking equipment, no stove, bad food, and damn little of even that. We didn’t fish and I never opened the book. Fred, bless his heart, looked to me as the supposed expert. As a result, his packing was just as bad as mine.

We drove to Yosemite Valley and slept overnight by the car parked at Happy Isles. The first day we hiked eight or so miles up the mist trail past Vernal and Nevada Falls into Little Yosemite Valley. We barely managed to eat portions of horrible cardboard food. The second day we hiked up to Merced Lake, another gorgeous hike, another ten miles, and another badly organized campsite with a barely acceptable fire and barely edible food. The third day we hiked up through Boothe Lake and Emerick Lake to Vogelsang. That was the third day of just a small ration of almost inedible food. The views and the hikes were gorgeous, everything I’d dreamt of during the long year since my last time up in the high mountains. And the headaches were constant.

On the fourth day we hiked down from Vogelsang to the road at Tuolumne Meadows and hitchhiked a ride from there down to Yosemite Valley, where we picked up Fred’s car and drove back down in defeat. Although the all-you-can eat Smorgasbord restaurant in the outskirts of Merced was a welcome consolation. That became a mainstay for the drive home for many other trips.

In 1964 Mom and Dad moved me from the public Awalt High School to the private Catholic all-boys St. Francis high school. I took that as being about me turning hippie, left-wing radical, even as a 15-year-old kid. But I don’t remember objecting that much. I guess I was compliant.

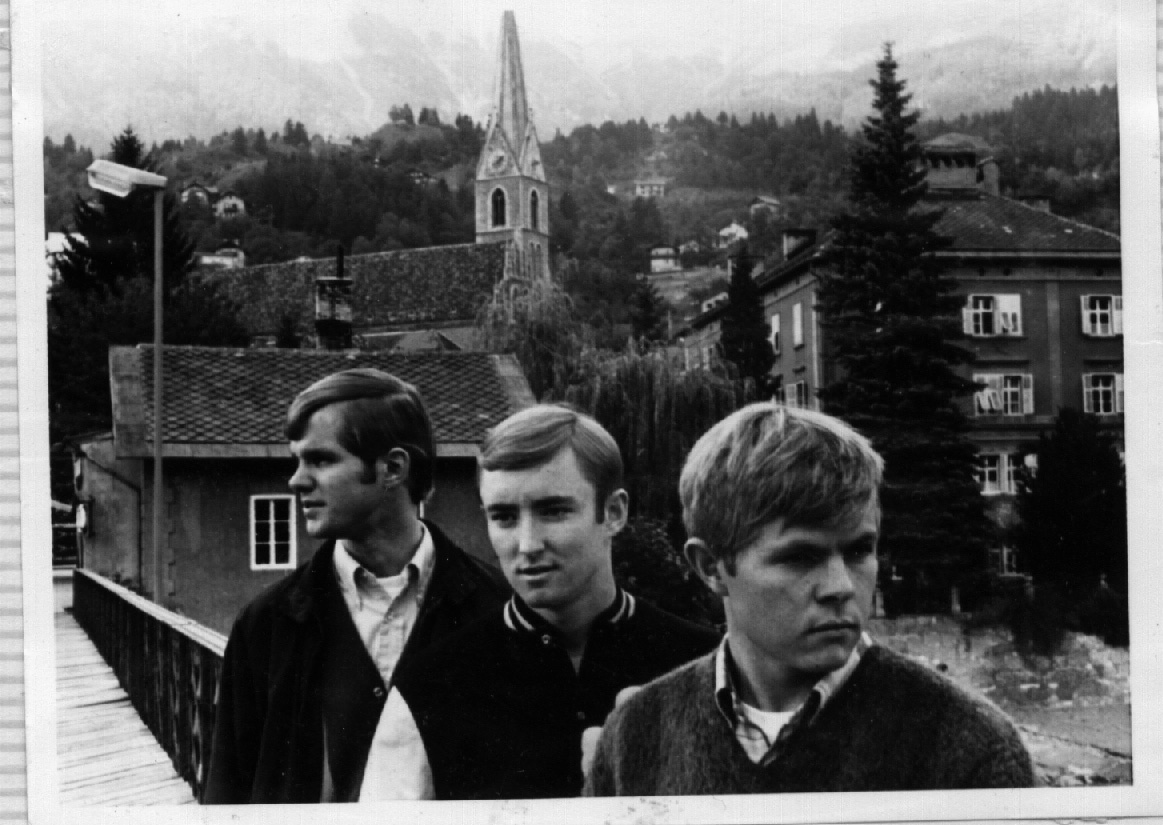

However, a funny thing happened when I started at St. Francis. I found friends there fast. George, Tom, and Bill became really good friends. We hung out together on weekends, even went backpacking together. George was best man at our wedding. The girls from Holy Cross High School, a mile up the road, joined us for dances, extra-curricular activities, school plays, and so forth.

That would not be the first time I’d have my school changed to straighten me out.

That fall Chip left for Pomona College. They didn’t drive down to Pomona to leave him off or fix up his dorm room. They put him on a plane at the San Jose Airport. As we drove to the San Jose Airport, Dad lectured Chip to not be a tight ass. “When the guys go off for a drink, go with the guys. Don’t be the only one who didn’t.” That was a reflection on Dad, and things he missed during his college years. I found it oddly humorous: both Dad saying it, and that it might have needed to be said.