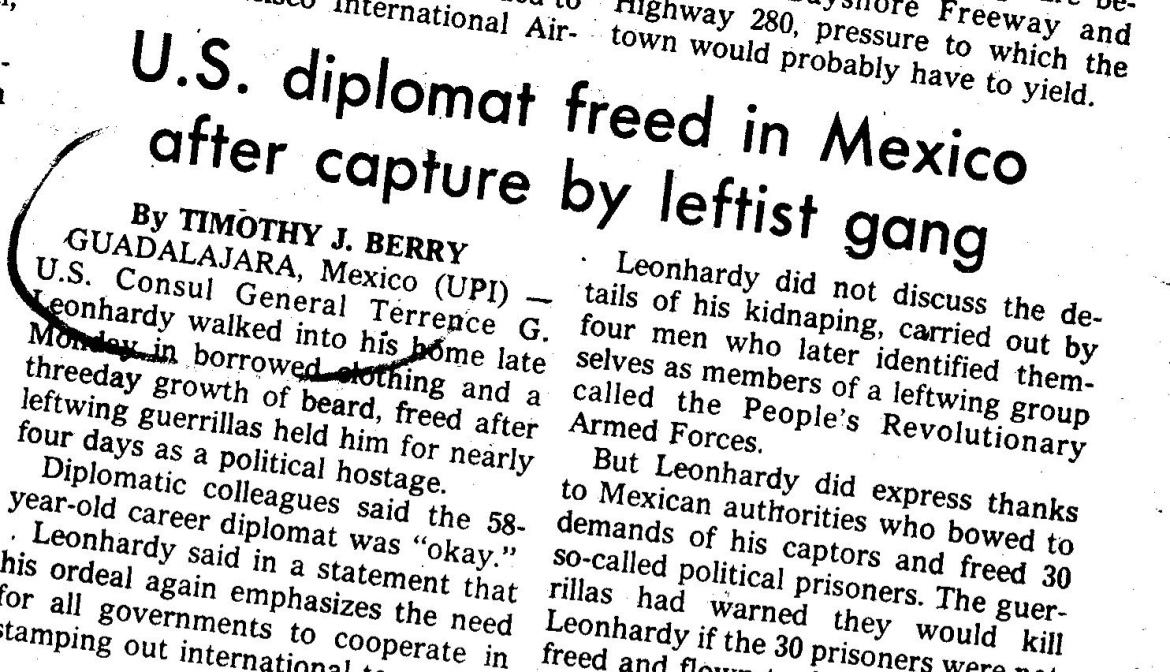

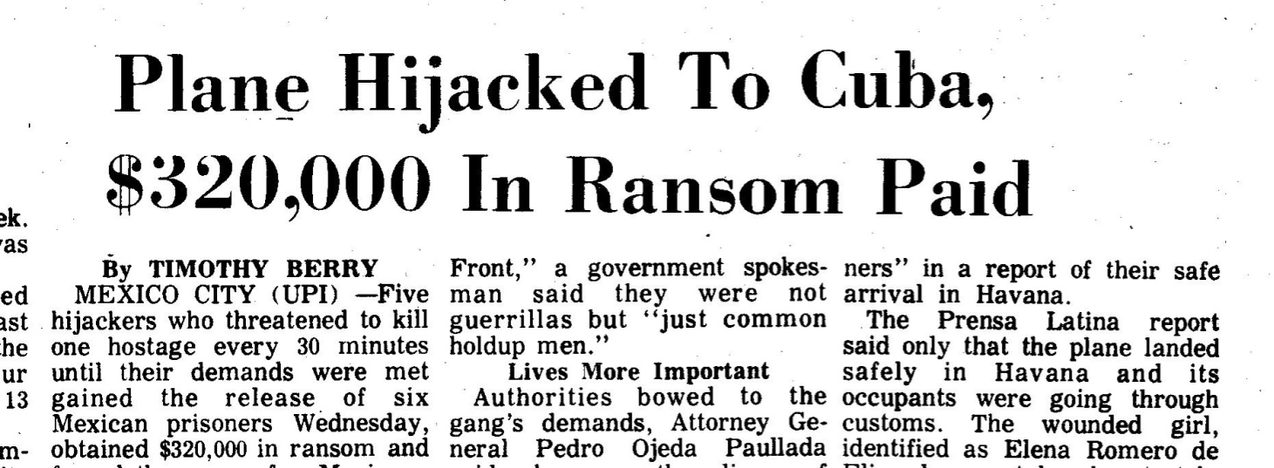

April of 1973. It was two or so in the morning. Pleasantly warm. I walked the paths that crisscrossed the interior gardens of the El Camino Hotel in Guadalajara, where I was staying. I couldn’t sleep, for a combination of stress and excitement. The El Camino was at that time the best hotel in Guadalajara, different from most, mostly horizontal. Connected wings of two or three stories of rooms looked over a series of interior gardens. I was there as a foreign correspondent, from the Mexico City office of United Press International, covering the state visit of Chilean President Salvador Allende to Mexico.

I came upon a small group in the lit garden, seemingly chatting, despite the hour. A man sat on a bench and 10 or so others sat on the ground, surrounding him. With a wave, the central figure invited me to join the group. The others turned towards me as I approached the group. And as I did, I realized that the man on the bench was Salvador Allende himself. Allende without advisors or security.

He asked me about me. I told him the truth: American, journalist. Looking even younger than my 25 years, and speaking fluent Spanish. He paused for a thoughtful second, then said (in Spanish, of course) something like “We are just talking. This is a group from the University of Guadalajara. And you are welcome to join, but as a young person, not as a journalist.”

So I sat down in the garden, and shut up, and listened.

And what was striking, what makes this remarkable even decades later, was how genuinely this great man shared himself with that group; and what he had to share. He was legitimately, sincerely, out to change the world. But, unlike so many others, not by any means. He was going to do it the right way. Using true democratic process.

For example, at one point he said Fidel Castro, his political ally, told him “to keep power, you have to kill like 500 guys.” (“Para mantener el poder, hay que matar unos 500 tipos.”) But no, he said, then he would just be another dictator, like all the others. When in fact (and this was fact) he had won his presidency in a true democratic election. He was there because the people voted him there, and — he was so inspiring — the time had come for real change, actual power to the people, because the people wanted it. Not just because somebody who had seized power wanted it.

Earlier that day, I’d attended and reported on a speech he’d made at the university. I was spellbound. His Chilean accent made his Spanish sound like poetry to me. And, much more important, his words, and his style, were deeply moving. He took on a hushed voice, almost quiet, when he talked about how his movement grew in the silence of the mines. Miners giving their lives, day by day, to enrich the mine owners (most big American corporations; he didn’t have to say it). And people wanting change. I had chills on the hairs of the back of my neck. And then he would up the volume, slowly, as he talked about the movement (the Chilean Socialist Party) grew slowly but steadily, a movement of people. And, as it grew, demanding change and power to the people, its opposition grew. His voice rose to a crescendo as he accused the United States, big business, and the CIA of doing everything they could to overthrow him, his party, and the Chilean constitution.

He treasured the Chilean constitution like patriotic Americans treasure the US constitution. It was a higher power than the political parties, international intrigue, his own party, or his opposition. And it was, in fact, in 1973, a working democracy that was 63 years old, had survived dozens of elections, and frequent changes of leadership and parties in power and parties in opposition. It was at the time the third oldest democracy in the Western Hemisphere, behind the United States and Canada.

That earlier Allende was Allende on stage, facing cameras, news media, a whole flock of professional politicians Chilean and Mexicans, plus a big auditorium full of students. That was also Allende in history, facing his place in history and his struggle to stay in power and protect his constitution from the business-driven power of the United States. That was the man I was reporting on during a state visit of Mexico.

What I discovered, in the garden in the small group, from two to four am, was that the real Allende was the same man. He wasn’t facades and personas. I believe I could tell. He was a brilliant man, and his power grew in the roots of his vision, his ideals, and his integrity. I dealt with politicians for almost a decade, as a journalist, out of Mexico City. I sat across the table from Mexican presidents several times. I interviewed Fidel Castro, Henry Kissinger, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan, among others. Castro had as much charisma, Kissinger had as much intelligence; but Allende was an idealist. He lived it and succeeded in building on integrity and ideals. And that’s what I saw, believed, and still believe.

Allende was a brilliant man, a true leader, an idealist, and a spellbinding speaker. He’d worked tirelessly for decades to oppose the US hegemony in Chile and Latin America, and the power of the wealthy upper crust and industrial monopolies. and Chile’s 1971 presidential election made him the first democratically-elected socialist head of state in history. And Chile was at that time the oldest constitutional democracy in Latin America. One thing was Russian and Chinese control of Eastern European and Asian satellite nations; and Cuba too. Having another Latin American nation “go communist” was an insult to the US, the Nixon administration, the Monroe Doctrine, and our national identity of good vs. evil. And soon after winning, Allende, true to his ideals, and supported by a like-thinking legislature, nationalized the mining industry, which meant confiscating the immense Chilean assets of big American mining conglomerates. The USSR sent money and resources, and Cuba sent hundreds of advisors. The US sent the CIA, its dominance of the continent, big business, and its wealth and power to get Allenda out. It was like 1914 with all the powers lined up for or against, and Allende and Chile the focus.

And, in the end, Allende was a tragic figure. My brush with him was in April of 1973. On Sept. 11, 1973, he was killed in the presidential palace by Chilean military troops under the command of Gen. Augustin Pinochet. Allende and the Chilean constitution were — exactly as he feared, exactly what he worked against — overthrown by the military with huge support of the CIA and the US establishment. He didn’t take Castro’s advice. He didn’t kill “500 guys.” He didn’t resort to dictatorial tactics. He didn’t change the world the right way, true to his ideals. What he did do was die trying.